Contrary to popular perception, Jews have been defending themselves and fighting in armies long before the State of Israel.

Review of: Derek Penslar, Jews and the Military: A History, Princeton University Press, 2013.

Let me start with a personal story: when I studied in high school in Israel, I thought that between the Bar Kochva revolt and establishment of the Zionist ‘Haganah’, Diasporic Jews were perpetual victims. Either because they were pacifists or simply because they were physically helpless, they died as passive martyrs in the Middle Ages, in pogroms and during the Holocaust. The Diaspora Jew seemed to me to be weak in both character and strength, one who was incapable and maybe even unwilling to defend himself on the most basic human level.

This historical image is still quite prevalent in Israel and abroad. Ironically, it serves both Zionist and anti-Zionist ideologies. Zionists can claim that they are the ones who rescued the Jewish people from their weak and pathetic state as permanent victim and provided them with the tools to determine their own destiny. On the other side of the coin, for Diasporists and anti-Zionist liberal Jews, particularly those in universities worldwide, the image of the weak, “womanly” or “sissy” Jew who abhors violence serves as an ideal and noble counterpoint to what they see as an increasingly barbaric and brutal State of Israel.

Professor Derek Penslar’s book Jews and the Military: A History shatters this simplistic image. The book, an historical survey of the relationship between Jews and military forces in the Middle Ages and the modern period, is the very model of historical synthesis. Combining primary material, pioneering studies and a broad, comparative perspective, Penslar provides the reader with a rich, complex and far more fascinating picture than the simplistic stories of passivity and martyrdom so prevalent in public discourse.

Passivity is not Pacifism

One primary anchor for the accepted view of the Jew as a completely passive figure is of course the famous religious principle of the “Three Oaths”, according to which Jews are forbidden to rebel against other nations or try to conquer the Land of Israel before the coming of the Messiah. Rivers of ink have been spilled on just how binding this principle is. However, as Penslar makes clear, even if it is true that most Jews objected to rebellion or wars of conquest, this does not in any way mean that Jews were opposed in principle to any form of violence whatsoever, including in self-defense. Indeed, traditional halacha never banned violence, even killing, if that was the only option to defend individuals or communities. When Jews could defend themselves against violence – be it during the Crusades or elsewhere – they did.

Jews in Christian countries carried or at least owned weapons including swords and firearms. In kingdoms such as Poland-Lithuania, Jews participated in their towns’ civil guard; in the frontier regions of that kingdom, synagogues themselves were fortified and sometimes even sported artillery. True, Jews were not particularly enthusiastic about wars, but then neither were most participants in warfare in the Middle Ages such as impressed peasants; only kings, nobles and mercenaries really benefited from organized violence.

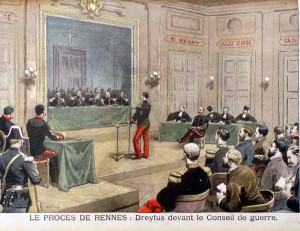

Not Just Dreyfus and the Czarist Army

All this changed in the Modern period and especially in the 19th century with the decline of mercenary and impressed armies. In their place came large-scale national armies made up of citizens enjoying equal rights and subsequently willing to make the ultimate sacrifice for their homeland. Here, ostensibly, was the chance for the Jews of European countries to “fight for their homeland”, not just to prove their loyalty but also to disprove the anti-Semitic canard that Jews are womanly cowards and disloyal traitors. On the face of it, this is a story of Jews emerging from mere passive defense to an active and even enthusiastic encounter with military force – an historic link connecting the relatively dormant Jewish Diaspora to the activist Jewish State.

However, primarily in the wake of the Holocaust, this story was swallowed up in an overarching narrative of Jewish victimhood. According to this narrative, Jews who tried to join European armies met rampant anti-Semitism and discrimination. Perhaps the most famous example of this is Alfred Dreyfus, who in spite of his talents as an officer was not accepted as an equal and was ultimately castigated as a traitor. If that was the situation in Western Europe, all the more so in the Russian Empire where most Jews lived: there Jews were forcibly conscripted at a very young age and compelled to assimilate; Jews subsequently did everything they could to dodge the draft – whether by fleeing, bribery or self-mutilation. The Jewish attitude towards army service was thus understandably ambivalent if not outright hostile.

Now, this narrative contains more than a grain of truth; most European armies were indeed permeated with anti-Semitism to one extent or another. Prestigious army Corps such as the cavalry, which was often reserved for people of noble origin, were largely closed or very hostile to Jews who wanted to join. The Czarist army was not Jew-friendly, and the fact that most Jews therein did not assimilate outright but often formed their own unique version of nontraditional Russian-Jewish identity was probably cold comfort to their often more traditional parents.

But as Penslar makes clear, this is only a small part of the whole story. First, not all Corps were monopolized by the nobility. For instance, in the Engineering and Artillery Corps of many European armies, where the emphasis was placed on education and merit, Jews were very successful. Furthermore, most French Jewish officers did not suffer Dreyfus’ fate. Most of them, both before and after the Affair, successfully integrated into both the regular and reserve parts of the French Army. Contrary to common belief, many of them were not the stereotypical assimilationist non-Jewish Jews, but sons of Rabbis and community leaders who not only established Jewish families but also received their communities’ enthusiastic support and blessing.

Even more importantly, most European armies were not as hostile to Jews as the Czarist army. Indeed, the ultimate counterpoint to the hostile Czarist army is the Austro-Hungarian Imperial Army, perhaps the most Jew-friendly military institution at the time. The multi-national Central European Empire invested a great deal of energy and resources to accommodate the many minorities in its territory, Jews included. There were more Jewish chaplains in the Austro-Hungarian Army than any other European army at the time, and Jewish religious requirements received consideration on a scale that was probably only exceeded by the IDF.

The same is true of the Jewish attitudes towards their countries’ armies outside the Russian Empire. Everywhere Jews could integrate into the army as equal citizens, even if only potentially, they did so willingly and enthusiastically. Jewish leaders and publicists repeatedly stressed the heroism of their fighters as the ultimate rebuttal to anti-Semitic claims of “Jewish cowardice”. Jewish officers often challenged their non-Jewish counterparts to a duel for anti-Semitic insults, and photos of Jews in military uniforms were something to be proud of, not ashamed.

Long before Zionism, Jews throughout the world spoke of their fighting brethren as the “new Maccabees”, cultivating every story of Jewish heroism in foreign service from Alexander the Great (!) until their own day. The Jewish veterans of the German army, for instance, were far from the liberal and somewhat pacifist image provided by their intellectual counterparts, and Jewish veterans elsewhere were little different in that respect.

From Wars Between Brothers to Wars for Brothers

But there was another, darker side to the story of Jewish integration into European armies, one which cooled their enthusiasm for war: the fact that their own brethren were often on the other side of the front line fighting for the enemy. There is a common story of a Jewish soldier in a European war – the army and the war change from version to version – who storms the enemy line and bayonets an enemy soldier. In his last moments, the enemy soldier says “Shma Yisra’el” and the Jewish soldier draws back in horror at the realization he has just killed another Jew. This story, which dates back to at least the Franco-Prussian War of 1871, has been told in many versions up to and including WWI. It stressed just how much European wars were also – inadvertently – wars between Jewish brothers.

Penslar notes that there is no documented case of this ever happening, but the very fear of its possibility troubled the minds of many Jews serving at the front and at home. Quite often, this fear prevented Jews in European countries from engaging in the kind of eliminationist rhetoric towards the enemy that informed many a European war, as one cannot truly hate one’s brother even if they fight for the “wrong side”. Jews would pray for their country’s success but not for the “total destruction of the enemy”, they often spoke of the need to “act as a Jew” when the enemy surrendered and they worked hard for the welfare of Jewish POWs from the other side.

As Penslar shows with flair, the Jews developed a kind of global “local nationalism”, of pride in the service of Jews on any side of a war – even if the sides opposed each other. This process reached its peak after WWI, when Jews on all sides fondly remembered Jews who served on both sides of the line – in the lists of those who died, in the fraternal and friendly relationship between veterans’ organizations and in the generally increasing worldwide Jewish solidarity.

But did not the Holocaust destroy the connection between Jews and armies and force them to become helpless victims? Penslar argues convincingly in the negative: Jews simply moved into a new phase, from wars between brothers to ‘Jewish world wars’, in which the Jewish people rose as one (or almost as one) for their brothers in peril. Already during and after WWI, Jewish veterans organized self-defense groups to protect their communities from anti-Semitic attacks. Before he died at Tel-Hai in 1920, Zionist hero Joseph Trumpeldor organized Russian Jewish soldiers to help protect Jews in St. Petersburg during the turbulent days of the March Russian Revolution and the November Bolshevik coup d’état. He even dreamed of taking his forces across the Caucasus Mountains to conquer the Land of Israel.

This new phase reached its peak in WWII, when much of Jewry was threatened with outright destruction. The debates about Jewish conduct and options in the camps and ghettos will no doubt continue, but one thing cannot be disputed: around one and a half million Jews fought the Nazis in one capacity or another. A third of these fought in the Red Army, another third in the American Army and the remainder in other regular armies or as ghetto rebels and partisans.

The view of WWII as a ‘war against Amalek’ – the Nazi army and its allies – in which (almost) no Jews served, were a focal point of struggle for Jews outside of Nazi-occupied Europe. Penslar describes in detail the enthusiasm of Jews around the world to fight the Nazis in any way possible. It was a truly global experience, which did much to strengthen Jewish feelings of solidarity and responsibility and which overwhelmed the often ambivalent and conflicting emotions they felt during WWI and before.

Penslar argues that the Israeli War of Independence in 1948 should be seen in the same light – not as a local war between the Jewish Yishuv and the Palestinian Arabs and their allies, but as a ‘Jewish world war’. In this war, the ‘front’ was in the Land of Israel, but the logistical ‘rear’ was the Jewish people and its resources throughout the world. There is much to support this view: Diaspora Jewry provided critical support during the war, including manpower, money and military and non-military equipment. Many of the officers who served in the Haganah and later in the IDF received their training in European armies. Jews came from all over the world to help fight the war, this time not to earn the recognition and respect of their host countries but rather to ensure Jewish independence. Penslar’s view is thus logical not only from a purely historical point of view but also as a means of strengthening Israeli-Diaspora ties.

Not the Final Word

Jews and the Military is a monumental and revolutionary work; it will no doubt set the historiographical tone for many years to come. However, it is not without flaws. Some of these are just eyebrow-raising, such as the dating of the Balfour Declaration to December 1917 (!). Furthermore, there is a tendency in the book to stray into interesting but marginal side issues, perhaps inevitable given the many fascinating finds one uncovers in a pioneering study such as this. Nevertheless, as interesting as debates about the Bergson group or the factual accuracy of American Jewish Zionist descriptions of the 1948 war are, they take up space better served by issues more relevant to the book’s main thesis.

One such issue which would have been benefited from more in-depth treatment is the question of Jewish service in the Red Army, both in the Russian Civil War and WWII. Contrary to what many think, the Jewish Red Army experience goes far beyond a few old men with their medals during V-E Day. It is doubtful whether there is a Russian Jew who does not have a relative or relatives who served and likely died on the Eastern Front – in the Barbarossa encirclements, the ‘meat-grinders’ of Rzhev and Stalingrad or the long and bloody road towards the ‘liberation’ of Europe and Germany. These events are a crucial part of many Russian Jews’ historical memory of the war, and they go far deeper than the simple view of the Red Army as liberators and victors.

Even more importantly, Jewish enlistment into and service in the Red Army, in both the Russian Civil War and WWII, is one of the most morally complex issues in Modern Jewish history. Their reasons for doing so deserve much more thorough treatment than that given here. The same goes for the often ambivalent attitude of Jews in the USSR home front, who were just as enthusiastic as their American brethren to fight the Nazis, but who worked for a monster no less ruthless than their enemy. The primary and secondary materials for such research are freely available, and I would have gladly waited another year or two for this important episode to be properly fleshed out.

Another issue is what feels like the author’s not very sympathetic attitude to Zionism and Israel in the book. There’s a clear difference between Penslar’s careful and nuanced approach to issues involving Jews in the diaspora and his far less balanced approach to Israel. The ‘Epilogue’ in particular reads far more like an apologetic pamphlet singing the diaspora’s praises – of the kind the author documents frequently – and far less like the reasoned judgment of a senior historian.

Take for instance Penslar’s accusation that the diaspora’s contribution to the 1948 War is not taught in Israeli schools or in tours. I’ve not done a study myself, but surely such an accusation needs to be backed up by copious evidence or at least a comprehensive survey of materials – and these are not provided. The argument that we know relatively little in the historical literature on the subject was news to me – scholarly articles on Jewish volunteers, arms and money have been published fairly frequently and in establishment journals for decades now; books on Jews in the Red Army and American arms supplies to Israel were both published by the Israeli Defense Ministry.

These accusations feel like a classic case of a revisionist overcorrecting the traditional historical picture. The same is true of Penslar’s constant emphasis on the continuity between the Jewish military experience in the Diaspora and the dilemmas the Israeli Army presently faces. While the continuity unquestionably exists, there are elements of the IDF experience which if not revolutionary certainly constitute a major break with the past: questions of high policy and strategy, identity formation as a sovereign majority nation, treatment of minorities and more. A brief look at the volume, depth and sheer variety of halachic questions asked and answered by Rabbis after the establishment of the State as opposed to their relative paucity beforehand would show just how Penslar’s view of a smooth continuity between periods is far too neat.

All this is not to detract from what is a stellar historical achievement of the first order, one which I hope will stimulate interest in this fascinating subject. If I have reservations, they are in that hallowed Jewish tradition of critique and continued debate, a tradition no less Jewish than the use of physical force and warfare.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

I would be interested to know if Penslar takes any note of WWII Jewish partisan activity such as the Bielski Partisans in Poland, a most interesting and under-studied phenomenon