Bogie Yaalon, former IDF Chief of Staff and present Defense Minister, helped shape the IDF's backwards and strange doctrine of avoiding military decision.

It was not mere hesitation: the IDF's performance during 'Protective Edge' derived from an entire doctrine which prefers not to decisively defeat terrorism • This doctrine is based on a post-modern convoluted method of thinking which dominated the IDF in the 1990s and which was a major cause of the IDF's dismal performance in the Second Lebanon War • The man who led this Backwards Revolution in Military Affairs was then-Chief of Staff Moshe (Bogie) Yaalon • It took many years for the army to repair the damage • Then Yaalon came back

At the height of Operation Protective Edge, Defense Minister Bogie Yaalon visited the settlements of the Gaza Perimeter to talk to the residents. During the talks, later publicized in the media, Yaalon said as follows: "We need to see how we maneuver this to a political settlement…it will come eventually"

This is how the Defense Minister summarized the strategic goals of the southern campaign: a political arrangement of unclear details to happen at some unspecified time, brought about by an attempt to wear down the other side. "We are in a campaign. It has political aspects, it has military aspects, there's also a very important aspect of the endurance of the settlement [in the war zone]," Yaalon explained to the exhausted residents, and declared "Hamas will be exhausted before we are exhausted."

According to Yaalon, then, the war against Hamas in particular and perhaps terrorism in general has almost no concrete military objectives. It has military "aspects", of course, but they are part of a larger campaign, the "bigger picture", the strategic picture, which is in the other spheres, specifically the political and that of societal endurance in wartime. Within such a framework, the ability to end the campaign is not in the hands of military forces – say by maneuvering to and destroying the enemy's Clausewitzian center of gravity – but in the hands of politicians and thinkers, who are in charge of "political arrangements" and "determination and standing fast [of society]."

One can easily find the fingerprints of this approach in the IDF's conduct during Protective Edge: the ground operation itself began ten days after an aerial bombardment meant to convince Hamas that "escalation doesn't pay." During this period, tens of thousands of reserve soldiers were called up and held in staging areas with nothing to do and no clear mission or purpose. As far as Yaalon was concerned, the operation could have ended there, with Hamas "regretting its actions" after being pounded from the air for a week and a half.

Even the existence of the tunnels was not supposed to affect this plan. "We thought: either we'll continue this action in our territory without risking soldiers, or we'll reach a ceasefire which will provide a political way to neutralize the tunnels," Yaalon explained in at a conference conducted by the BESA center on the operation. "As long as a terrorist attack from a tunnel wasn't actually realized, it was possible to accept a cease fire even in such a situation." He explained: "Just as we could accept a cease fire with Hezballah even though it has an arsenal of rockets, because you can deal with this through political and other means. So, here, too: in the framework of a cease fire we can deal with this threat as well."

Only after enormous pressure from cabinet ministers – and only after Hamas showed a willingness to use the tunnels in battle – did Yaalon order a limited ground offensive. The purpose was not military decision, of course, but only to "deny Hamas threatening capabilities", something which was supposed to require only require a few days.

Thus, after the IDF finished destroying the tunnels "we know about", we could finally go back to normal, withdraw the ground forces and continue the campaign of aerial attrition and televised maneuvers for a political settlement. Gantz gave his infamous "Speech of the Poppies", someone in the army spoke of a "security belt", and everyone was itching to release the reservists before the vacation period in August. True, it took 22 long days of rocket and mortar fire, but eventually the goal was achieved: "it came eventually."

This, then, is the IDF of 2014: an army which avoids military decision, is hesitant to act and tries to get the enemy to change its behavior with semi-military pressures and "political maneuvers."

Why did the IDF avoid defeating Hamas outright? And why do the heads of the IDF speak of fighting a local terrorist organization as though it were a Cold War between superpowers?

To understand the answer, we need to go back to the foundations of Yaalon's security outlook and his military-intellectual background.

Shimon Naveh's Post-Modern "Revolution in Military Affairs"

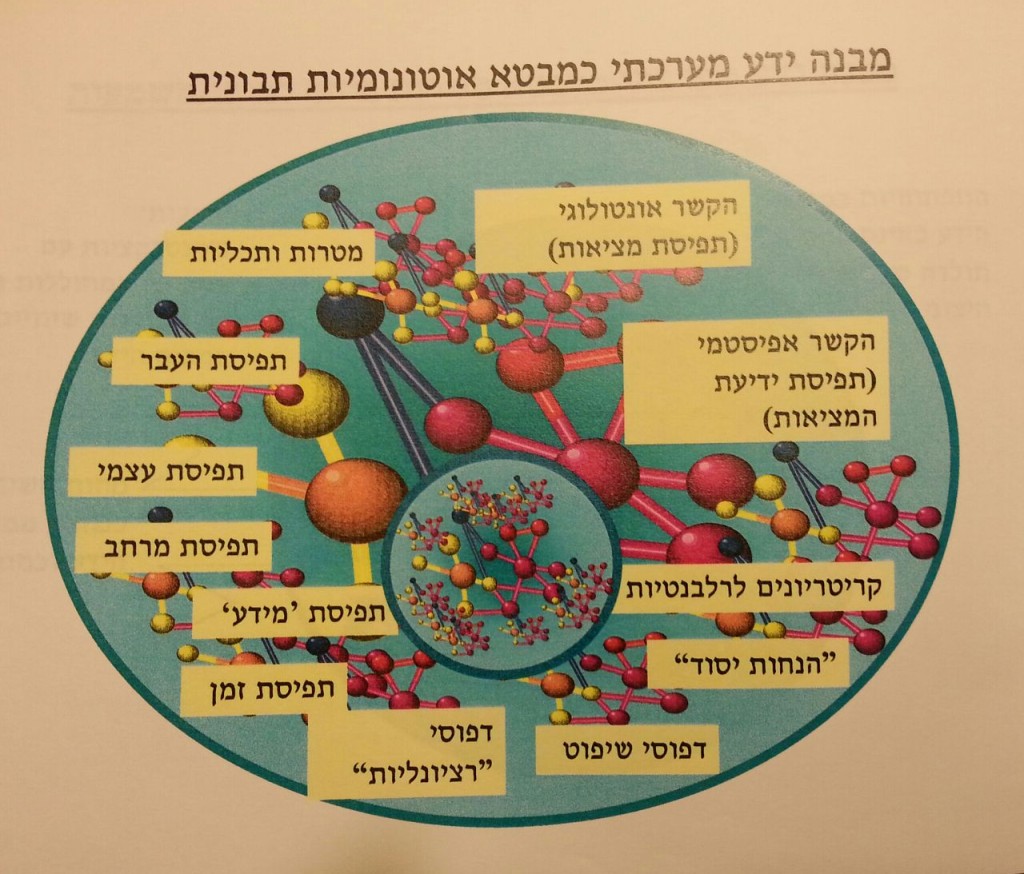

Yaalon's conception of military force came from a special institute for military thought founded by Brig. General Dr. Shimon Naveh and Brig. General Dov Tamari in 1995 known as the Operation Theory Research Institute (OTRI). This institute was meant to develop original ways of military thinking and cultivate these among the IDF's senior commanders. An admirable goal, in practice the Institute dabbled in convoluted post-modern casuistry, using terms that were extremely broad and which belonged more in a philosophy department than an army; the term 'epistemology' is repeatedly used in the Institute's writings.

The brains behind the OTRI was undoubtedly Shimon Naveh, whose doctorate involved abstract analyses of military maneuvers – transforming them from concrete historical events with geographical, technological and human constraints into various types of geometric maneuvers taking place on an imaginary plane.

In Naveh's Book, In Pursuit of Military Excellence: The Evolution of Operation Theory, as well as in his various articles, one can find a plethora of vague phrases like "neutralizing the internal linear logic" or the desire to "protect a strategic formation with minimal strategic depth and maximal friction space in conditions of quantitative asymmetry."

The purpose of these thought exercises was to turn the military profession into a pure intellectual exercise, a kind of mathematics of the use of force, and provide deeper philosophical meaning to the content of military activity. In this context, Naveh redefined classic strategic terms, drawing inspiration for this from post-modern philosophers, and granting a great deal of weight to subjective consciousness and casuistic and sophistic interpretations of reality.

Thus, for instance, Naveh fiercely objects to the accepted distinction between "victory" and "decision", arguing that decision – an objective, physical action of destroying enemy forces or conquering territory – is entirely unimportant, since victory is defined by the subjective goals of each side. Thus there might be a situation where both sides "won".

There's no doubt Naveh was an impressive man – a tall and intelligent man who stood out in the often anti-intellectual atmosphere among Israel's officer corps. People who learned by Naveh describe a sharp and educated teacher, who commanded many languages and knowledge and possessed rare connections with generals and intellectuals around the world. Armed with unusual bluntness – even for the traditionally rough-and-ready IDF – and possessing of a huge ego, Naveh had everything needed to attract young and intelligent up-and-coming officers.

"I sh*t on everyone"

Naveh was not just a critic but an innovator. In his doctorate, later published as a book, Naveh expanded on what military thinkers call the "operational level of war" – the intermediate level between the policy of politicians and the tactics of the combat units.

Since he was the (ostensible) founder of a "school" on the subject, he could turn condescension into a profession. According to officers who studied under him, Naveh had a frequent tendency to overcomplicate subjects, spending several minutes in a "titanic effort whose whole point was to complicate and become lost…to be long where he could short, to confuse where he could clarify, and to sow irreparable intellectual destruction in any idea which preceded him and had explained it simply and clearly."

No surprise, then, that during the entire time it operated, the OTRI did not publish a single document which could be considered a binding and orderly distillation of its recommended doctrine: the few products of the OTRI were never distributed – only placed in a "learning materials room" in the Command and Staff College, far from serious scrutiny.

As befits an uber-intellectual, Naveh never tested his students or assign final papers. All students received a 100, or a 'Pass' grade, and sent back to the ranks without anyone trying to check if they even understood the post-modern-cum-strategic word salad they'd been hit with.

One can learn something of Naveh's personality from an interview he gave to Yotam Feldman of Haaretz a few years ago. In this extensive and in-depth interview, Naveh didn't spare anyone from his lashing tongue: Shaul Mofaz "stinks, is an idiot but is a terrifying bastard"; Yaakov Amidror is "a pathological liar, a pretender, a complete bum, a chatterbox"; Moshe Kaplinsky is "an idiot, a kind of dunce." Even former State Comptroller was in his crosshairs: "I tell him, go to hell, you're an idiot, you don't understand anything." The rest of the army chiefs are of course "borderline illiterates…total nothings." Oh, and apparently, "most of the Jewish people are like that, like monkeys."

In short: "I sh*t on everyone, what do I care."

Naveh's imperious attitude led him to ignore all the accepted lines dividing the political and military spheres. Mr. Clausewitz-has-nothing-on-me and the self-proclaimed prophet of the operational level of war did not see himself as subject to the limits of ordinary men. Thus, without shame, Naveh spoke of how his leftist worldview affected the doctrine he shaped, as he explained in the Haaretz interview: "This war against the Palestinians needs to lead to their liberation," and his theory was meant among other things to "minimize damage on the Palestinian side."

Despite the esoteric nature of his complicated ideas – and the heaps of personal abuse he poured on many an unsuspecting senior officer – Naveh succeeded in gathering a small but devoted following of officers, who spread his ideas throughout the army. Officer such as Gal Hirsh, Aviv Cochavi, Gershon Hacohen and others who passed through the OTRI enthusiastically absorbed Naveh's ideas, thus making a significant impression on the army. But one officer stands above all in having opened the doors of the General Staff to Naveh: Moshe (Bogie) Yaalon.

Yaalon Opens the Door

"The OTRI made a contribution both to Central Command and the General Staff," Yaalon explained to journalist Caroline Glick in an interview for Makor Rishon in 2006, around the same time the Institute was being closed for irregularities. "The contribution to the IDF was expressed in developing a method of operation which was required by the development of threats," Yaalon added, as a citizen already eyeing a political career. He even attested that "through OTRI's work a situational assessment method developed which is used today in both the Commands and the General Staff."

Yaalon, who encountered OTRI ideas when heading Central Command, integrated Naveh into his thinking processes, allowing his esoteric ideas to penetrate the army and influence the formation of the conception of use of force in the field. When Yaalon became Chief of Staff, the door was now wide open for Naveh and the OTRI team to shape the security outlook for the entire IDF.

Those days, Yaalon formed an exclusive "thinking forum" around him, in which some of the senior staff officers and other external experts participated, which convened regularly in order to brainstorm and discuss strategic questions. Forum discussions were led by Maj. General (res.) Amos Lehman, an organizational advisor by training who was recruited by the Chief of Staff's office for the task of 'General Staff assistant for thought processes', and other officers, students of the OTRI, also participated even thought they were not part of the General Staff. For Yaalon, these meetings were a high point, as military journalist Raviv Drucker pointed out: "I'm addicted" he said at one of the meetings. "I don't understand how I reached such a high rank without such thought processes."

The fact that most of the General Staff officers didn't participate caused a lot of problems. "The group was kind of a 'shadow General Staff'", a senior officer, well-informed on the goings on in the General Staff then, told 'Mida'. "The feeling was that General Staff meetings were kind of a charade…while the real decisions were taken elsewhere." The 'Thinking Team', which sometimes convened in the OTRI itself, was an important stage in the embedding of Naveh's ideas in the IDF's operational doctrine.

The 'Limited Conflict'

One of the first fruits of Naveh's influence on the IDF was the formation of a new doctrine for fighting terrorism. In an article he published in the IDF internal journal Maarachot in 1998, Naveh explained that in light of the signing of the Oslo Accords, "the problem of the military planner has ceased to be finding an appropriate target [and] the choice of an appropriate tactical method [to achieve it]." In his opinion, the political changes caused the struggle against terrorism to have to "not only ensure greater security for the citizens of Israel, but also preserve the positive trend of the political discourse."

It's not just the peace process. In Naveh's opinion, the accumulation of a number of processes required a wholesale strategic re-evaluation. Social and political considerations such as "the world political order, the geo-political map in the region, Israel's foreign interests, the structure of Israeli society, Israel's national order of priorities," make Israel's classical security doctrine irrelevant, requiring it to be entirely rewritten.

Within a few years, these ideas became official doctrine in the IDF in what became known as the "doctrine of limited conflict." "The choice of whether to follow the path of the limited conflict or adopt a strategy of military decision or wearing out, is first and foremost a function of the evaluation of what of all this will allow us to achieve our political goal," explained Maj. General (res.) Nir Shmuel, the man charged with formulating the new doctrine in an article published in 'Maarachot', and in the spirit of Naveh stated that: "we should assume that in the conflict between us and the Palestinians, the strategy of wearing out serves us best."

Under the leadership of Yaalon as head of Central Command, the IDF knowingly abandoned the option of decisively defeating terrorism, limiting itself by choice to strategies of defense and "wearing out," in the belief that the real solution will come from the peace process and "changes taking place in the world."

Bogie Builds a Wall of 'Containment'

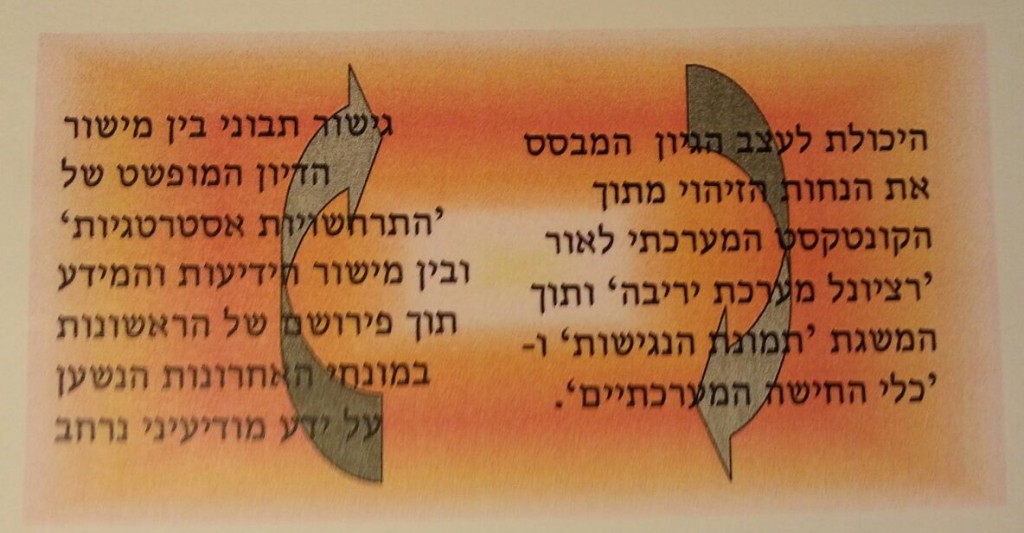

Yaalon explains the idea of blocking terrorism without defeating it in his book Derech Aruka Ketzara (A Long Short Road) in great detail. After explaining the strategy of 'containment' he adopted, which he calls 'building a wall', Yaalon explains that he arrived at it "through though processes which I conducted first in Central Command and then later in the Deputy Chief of Staff's office and the office of the Chief of Staff" (p. 109). These processes caused Yaalon to conduct a new method of analysis in the army. While the traditional method "was the evaluation of the engineer", in which the commander asked "practical questions from the field of construction: what kind of materials do you need and how much? What kind of companies do you need and what type of arms?" by Yaalon's lights, the task of the military leader's job is entirely different:

I argued that we can't just deal in engineering. As an army we can't just be contractors. We have to go from planning to design.We have to deal with architecture. Before we approach military activity, we need to deal with its formation. And its formation is cultural, conceptual…

And what is shaped in Central Command under General Yaalon? Read slowly and carefully:

We defined the connection thus: Israel and the Palestinians are Siamese twins joined at the hip. Israel is the stronger of the two, but is still joined to the weaker twin. The two are in a process meant to lead to separation. The path to separation is cast like a tunnel. Oslo paved the tunnel, and the international system wrapped it in concrete…

But Arafat is not interested. Arafat does not want to separate at the end of the tunnel, but to blow it up. Therefore a war will break out, in which our job will be to prevent Arafat's attempt to blow up the tunnel and leave it. Our job in the war will be to force Arafat back into the tunnel against his will…to abandon the path of violence and return to the path of negotiations.

Reading these words, one might forget that these were the thoughts of a sitting Chief of Staff, whose task was carrying out military objectives laid down by the civilian government. Not only is he pondering issues which are not his prerogative, but he's developing an entirely new security outlook – without the consent or even knowledge of the political leadership. Is that what Clausewitz meant when he established the supremacy of the political leadership over the military?

An Obsession with Political Breakthroughs

As we all know, the wall failed; Arafat did not return to the metaphorical "tunnel". Israel was forced to launch Operation Defensive Shield which eventually eliminated the PLO's terror capabilities and largely ended the reign of the suicide bomber. But in spite of the relative victory on the ground, Chief of Staff Yaalon was not satisfied, because the real accomplishment – a political one – was not reached: "the conflict has to end with the Palestinians admitting that violence doesn't pay" (p. 158). And how will we be sure that they "learned"? For that "an alternative to Arafat's terror regime" is necessary. And what is this alternative? "The government headed by Abu Mazen, established in 2003, created the opportunity to…strengthen the Palestinians whose path is not of violence…"

These thoughts, anachronistic though they are, indicate the degree to which Yaalon involved himself in political matters. He may not have ignored the real strategic goals of the PLO, but he nevertheless thought that "we succeeded in convincing it that the path of terror does not serve the Palestinian interest."

Yaalon didn't just concern himself with the attitudes of political leaders and terrorist organizations; he was also plenty concerned with analyzing Israeli public opinion and the degree of legitimization it granted the army. As he explained in a lecture he gave at the National Security College in 2001, when he was serving as Deputy Chief of Staff: "This struggle will be decided by attrition. We call it 'wearing out.' Each side is trying to exhaust, to wear out the other side. And to hold out, you of course need the capability to be steadfast." In this context, Yaalon attributed much importance to the media's role: "My accomplishment in this struggle is first and foremost not to be on the front page…that was the metric on which I based the evaluation of the brigade commanders. If you're on the front page, then something is wrong by you."

And how else does one avoid media attention, except by forfeiting the initiative and repressing aggressiveness?

In two places in his book, Yaalon points to cases where his estimation of public opinion affected his practical decision making.

The first took place in 2004, when the IDF launched an operation to detect smuggling tunnels which were already being dug to smuggle goods from the Egyptian side of the border. The air force attacked a series of houses sheltering tunnel openings, many of which were booby-trapped with explosives. During the operation, Israeli TV ran a story which harshly criticized the operation and Yaalon abruptly cancelled the operation. In his book (p. 144-145), Yaalon explains that he did so because he understood the "the consequences…of the loss of the Israeli consensus regarding this operation, in a manner which could affect in the long term the legitimacy Israeli society gives the IDF in its war against Palestinian terrorism." Therefore, he felt that it could be "winning the battle but losing the war."

Put differently, although Yaalon received no negative instructions from the political leadership, he cancelled a clear military operation because of his personal fears of the effects of one critical television story.

In another case, Yaalon missed a golden opportunity to attack a convention of Hamas leaders, including Sheikh Ahmad Yassin, Ismail Haniyeh and Mohammad Dief, because of the fear that an effective bombardment of the meeting would harm the adjacent building containing civilians. Therefore, Yaalon ordered a strike with inappropriate munitions, and the Hamas leaders – the 'Dream Team' – survived the blast. Here, too, Yaalon's fear of a media "Pyrrhic victory of delegitimization in the eyes of Israeli society" played a key role (p. 150).

Yaalon explained that he had no moral qualms about a proper bombardment, as these people were clear terror targets. He was only concerned about public relations and public legitimacy. This is how far Yaalon is willing to go in his "Doctrine of Limited War" and his obsessive focus on public consciousness. For Yaalon, the non-military considerations trump everything else. Indeed, they become the sole objective of the war. At the moment of truth, when the choice is between military and non-military considerations, Yaalon chooses the latter, and reins in the army.

But even per Yaalon's theory, this is pretty weak sauce: it's one thing to attribute so much power to the Israeli media and B'Tselem style protests – why so hesitant? Why does one solitary critical article suffice to cancel a single operation?

Intellectualizing Hezballah to Death

The best example of Yaalon's method of thinking came in the Second Lebanon War. In his book, Yaalon his explained his assessment of fighting on this front, based primarily on a cultural-religious analysis of Hezballah: "Hezballah is a social, religious, political and ideological phenomenon which has become an inseparable part of Shiite life in Lebanon…" Therefore, Yaalon explains that they cannot be defeated militarily in a single blow "because it cannot be uprooted from the hearts of its members or fans" (p. 204).

Based on these assumptions, Yaalon concludes that "Hezballah must be fought by taking advantage of it political weak points…that the organization should be weakened to the point that the Lebanese political system will know how to deal with it." For this, Yaalon invented the idea of "letting the rockets rust." It's supposed to work like this:

In the event of a Hezballah attack in the north, Israel should respond with an immediate air attack, the calling up of reserves and concentrating them in force along the northern border. If the air attack and concentration of ground forces move the international and Lebanese systems to apply political pressure on Hizballah to cause it to disarm in the future – so much the better.

If these moves do not have the desired effect, the IDF will have to move into Lebanon in a calculated manner and for a limited amount of time, seize controlling territories, stop the Katyusha fire into Israel and cause international and Lebanese pressure to lead to a cease fire which will serve our interests…

So the whole purpose of military operations is to "move" the international system to solve the problem, since only they can solve it. And for this, the IDF concentrates large forces to stand around and seem menacing without doing anything. Sound familiar?

Only if the concentration plan doesn't work should the IDF move over to a strictly limited ground maneuver, whose purpose isn't even military, but one of consciousness: seize dominant heights and let the political pressure work its magic. But what if that doesn't work? What if the IDF follows the non-existent OTRI book to the letter, as difficult as that is, and the terrorists don't bite? Yaalon provides no answer, at least in the book. "It will happen eventually", is the likely answer.

A War of Effects

These ideas had a destructive effect on the IDF's performance in Second Lebanon. The war which was already derisively known as the "war of effects", and whose purpose was to affect the enemy's consciousness rather than his military capabilities, which reached its peak (or nadir) at the battle of Bint Jbeil. The order Gal Hirsh distributed to his troops shows just how much these ideas became destructive at the practical level:

A large scale low signature infiltration…an ambush-quick stabilization on the dominating territories and creating lethal contact with built up territories, while creating shock and awe, freezing the area of activity and moving to control, while spatially and systematically dismantling enemy infrastructure.

Beyond the vague gibberish, one can discern the basic rationale: applying psychological consciousness-changing pressure on the enemy in the town, using special techniques for that purpose. Decision, conquest or physical destruction of forces are not the mission; "shock and awe" is.

Unfortunately, the enemy was neither shocked nor awed, so in spite of Hirsh's public boasting of capturing the town, and although our brave soldiers hoisted the Israeli flag over the municipality building, the terrorists continued to be active and deal our forces heavy casualties.

It's not hard to see signs of this approach during Protective Edge as well: concentration of forces; operational and 'consciousness-changing' air strikes; and even when the ground forces went in, it conducted an unsophisticated frontal maneuver, lacking finesse and inspiration. Because the entire purpose was to confuse the enemy, it is no surprise that decision played no part in the battle plans. Officers who served in Southern Command speak of planners looking frantically for a consciousness weak point of the enemy, constantly discussing policy questions like "who will replace Hamas." The fact that classical maneuvers like flanking, encirclement and destruction could also lead to pretty good results, was barely mentioned.

The closure of the OTRI in 2006 for financial irregularities helped the IDF break free of this insanity, but the return of Yaalon as Defense Minister has caused it to regress. If Israel wants to stop having round after round of "limited conflict" with Hamas, they might want to rehabilitate the old but proven Israeli doctrine of quick military decision. It may not be fancy, but it works.

English translation by Avi Woolf.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.