Henry Kissinger's "World Order" endorses balancing of power to check "globalist" forces like ISIS. Sadly, he isn't entirely clear how to do this.

Henry Kissinger's World Order comes at a time when most of the old international arrangements are collapsing · States created in the Middle East 95 years ago are falling apart, and an American President is giving up on the American role as the Strong Man who balances things out · Kissinger's book is not flawless, but succeeds in making order out of the new world chaos

Review of: Henry Kissinger, World Order, Penguin 2014.

It would seem that Henry Kissinger's World Order could not have come at a more appropriate time. With the Russian annexation of the Crimean Peninsula, the rise of ISIS wiping out century-old borders in the Middle East, and the pro-democracy demonstrations in Hong Kong, the need for a new formative theory of international relations is obvious.

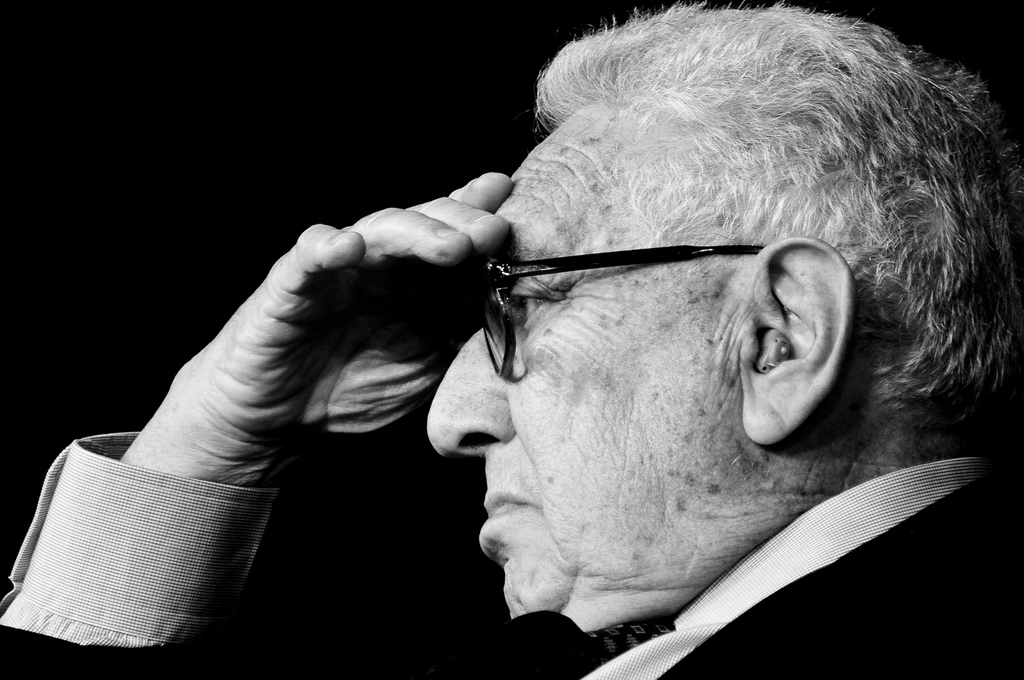

The global chaos which has broken out in the past few months in full view of Western audiences paved the ground for the return of the veteran Kissinger. Kissinger, architect of the world order in one of the darkest hours of the Cold War, is still here – and he has what to say. Recently he came out with a fierce critique of President Obama regarding his attack plans in Iraq and Syria – Kissinger was one of those who pressed for action.

The issue of the world order has concerned Henry Kissinger for his 91 years as a world statesman. The collapse of order and balance of power between the two world wars is what led Kissinger's family to flee Germany in 1938, on the eve of WWII. His doctorate at Harvard University's Department of Political Science was on the two great statesmen who shaped the European order of the 19th century – Castlereagh and Metternich.

As National Security Advisor and Secretary of State during the Nixon and Ford administrations, Kissinger conducted American foreign policy according to a method called Realpolitik. Among American foreign policy makers, he is the great realist, in contrast to the idealists such as George W. Bush who aimed to spread the values of democracy by force if necessary and isolationists who believed they could live behind Fortress America undisturbed.

Kissinger's realist policy bore great fruits including the establishment of diplomatic relations with China in the early 1970s and the establishing of détente with the Soviet Union. On the other hand, Kissinger attracted a great deal of criticism for the lack of values – and one might say scruples – in his handling of the foreign policy of the world's most powerful democracy.

Between ISIS and the Communists

In his new book, Kissinger traces the origins and evolutionary development of the nations of the world, finding how each nation's history shaped its view of the proper world order. Kissinger indeed presents a wide variety of such views, but then reduces all of them to only two categories: one based on a balance of power and a global world order. Thus, while the USSR in its time and the ISIS of today imagine entirely different world orders, Kissinger nevertheless calls them both "globalists" – as both the Communists and ISIS aim to go far beyond their borders, and effectively to dominate the entire world.

The second category of world order – and that preferred by Kissinger – is the order first developed in the 1648 Peace of Westphalia which ended the Thirty Years' War between Catholics and Protestants. This uniquely violent and disruptive war led all the powers of Europe to agree to mutual recognition of the sovereignty of all states as well as non-intervention in each other's internal affairs. As a result of the agreement, a balance of power was created which allowed all states to focus on their own narrow interests. Paradoxically, this narrow focus allowed for long period of peace and stability in Europe.

Per Kissinger, the strength of Westphalia was in the flexibility it enabled. When states act only in their own narrow interests, then alliances easily form and reform and ensure the constant existence of a balance of powers. The Westphalian model was best articulated by the British Prime Minister Henry Temple, Viscount Palmerston:

"We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow."

America the "Balancer"

The theses Kissinger lays out come at an interesting time. Barack Obama was elected president to a large degree as a public rejection of the idealistic policy of his predecessor George W. Bush, who supported the spreading of democracy including through military intervention in Middle Eastern states. Today, that same president is being forced by American public opinion into a military offensive against Islamist fighters.

Kissinger is elegantly but sharply critical of both Bush and Obama. On the one hand, Kissinger sees Bush's policy of spreading democracy by force as a "globalist" approach which he summarily rejects. On the other hand, Obama's seeming neglect of vital American interests in the Middle East is simply incomprehensible to a conservative-realist like Kissinger. Kissinger's advice a few weeks ago was to go big but go quick against ISIS, defining ISIS' actions as an insult to American values which cannot be ignored.

Kissinger accords an important role for the United States in the Middle East – the "balancer". According to Kissinger, the Westphalian order depends on the existence of a "balancing" player. That player needs to have significant power and a consistent policy – always supporting the weak against the strong. The "balancer" prevents the upsetting of the balance of power or allowing one side to truly crush the other.

The realist Kissinger warns against simplistic reliance on a balance of power based on religious differences (Sunni/Shiite), reminding his readers that history is full of examples of countries setting aside ideological differences to achieve strategic decision. Such was the case in the alliance of Catholic France and the Muslim Ottoman Empire in the 16th century – an alliance that caught Christian Europe completely by surprise. Therefore, Kissinger insists that the United States serve as the "balancer" instead of any local player.

But What of Globalization?

Kissinger certainly knows how to write. He makes complicated issues a joy to read about. The book manages to weave many historical examples without drowning in the sea of detail such cases can provide. The decision to divide the chapters in geo-political regions is a wise one which allows the reader to read in an organized manner and understand the key issues themselves. Nevertheless, it is not flawless; Kissinger doesn't really provide a full answer as to how a state-based Westphalian order can deal with globalist challenges like terrorism, mass immigration or climate change.

In addition, there are processes in the modern and post-modern world which undermined Kissinger's theory of a world order. Globalization, which has only accelerated over time, is blurring the social and cultural boundaries between countries. This distinction effectively serves as the founding assumption of the book itself. In a world in which protestors in Hong Kong share the same values as their American brethren so far away, it's difficult to speak of a global order based on unitary values. Finally, one can understand and even appreciate Kissinger's desire to avoid direct criticism of American presidents, but we could have done without the praise given to Bush, Jr. in a chapter which tears his foreign policy to shreds.

English translation by Avi Woolf.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.