A new documentary promises to finally tell the story of WWI from the Russian perspective.

Russia's participation in WWI has often either been told from the enemy's perspective or through the lens of the Russian Revolution • A new documentary promises to change this • The results are mixed—a detailed description of the fighting marred by nationalist and even pro-Czarist bias • A hundred years on, Russia still struggles with its past

Review of: "Первая Мировая" (English: The First World War) (English Subtitles). 8-Part Documentary. StarMedia and Babich Design. 2014. Available in full here.

Churchill called the Eastern Front of WWI "The Unknown War." If this is true, then the Russian Army in that war is very much the "Unknown Belligerent." To the extent that anyone writes about the Eastern Front at all, it is almost always from a German or at most Austro-Hungarian point of view, with a few Russian sources as a token counterpoint. In these narratives of battle, the task of the Russian army is to be a passive actor in its own story—without a face, without suffering, without humanity.

But Western prejudice alone cannot account for this lacuna. The truth is that Russians themselves—especially under the USSR—effectively ignored the war for almost a century. It was an embarrassment, a highly destructive capitalist-imperialist war fought for nebulous reasons. Russian-language works on WWII in the East continue to flood the market, but there is still barely a trickle for WWI.

Worse, far too many Russian and Western historians have viewed Russian participation in the conflict through what WWI don Hew Strachan called "the teleology of the revolution." In this view, the war was nothing more than a stepping-stone or catalyst for the "real story" of the revolutions and civil wars of 1917-1926. With the WWI centennial underway, the time has finally come for us to understand Russian participation in the war as an historic episode in its own right and on its own terms.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JhXKlYnSWjA&list=ELlzBS5WrPu4s

The benchmark for military documentaries. StarMedia's Soviet Storm.

When I saw that the Russian company StarMedia had put out a series on WWI and Russia's involvement therein, I was ecstatic. For those who don't know, StarMedia are the makers of Soviet Storm (Великая Война; English: The Great War)—one of the best documentaries on military history around. Through judicious use of computer graphics, personal stories, and actors, Soviet Storm gives the viewer a comprehensive lesson on the barbarity and sheer scale of the Eastern Front of WWII in language and terms anyone can understand.

Even better, Soviet Storm is a fairly honest and self-critical documentary. There's an entire episode dedicated to the horrific and largely futile battles of the Rzhev salient, which the USSR tried to pretend never happened. It also contains muted but honest references to the Soviet failure to evacuate civilians from Leningrad or Stalingrad, the rape campaign in East Prussia and Stalin's determination to prevent Poland from being a real democracy. StarMedia is thus uniquely equipped to tell Russia's story in the First World War.

When I started watching, I was fully prepared to endure the inevitable nationalist biases which pervade any official or semi-official history. If this documentary taught me as much about Russia's First World War as Soviet Storm taught me about the Second, it would be more than worth it.

So, how does it hold up?

An Unknown War No Longer

I'll start with what is unquestionably good with The First World War. StarMedia's gift for clear, understandable maps and graphics pays off handsomely. Viewers will learn in detail of Russian fighting on all the relevant fronts—against the Germans in Poland and the Baltic, against Austria-Hungary in Galicia and against Ottoman Turkey in the Caucasus and Eastern Anatolia. Just as Western Front enthusiasts know of Ypres, Cambrai, Verdun, and the Marne, viewers of The First World War will learn of Tannenberg and Sarakamish, as well as Lutzk, Erzurum, Lodz, and the Western Dvina.

StarMedia's "infoboxes"—brief interludes providing clear explanations of weaponry and tactics—is just as good if not better here than in Soviet Storm. In addition to general discussion of WWI weapons, the infoboxes include uniquely Russian innovations—tanks, armored cars, and air forces—as well as how the Russian Army used cavalry on a battlefield often dominated by machine guns. Sadly, the fascinating subject of Russian and Austro-Hungarian armored trains goes unmentioned. But that's a small, personal quibble.

Even more importantly, this series lets us meet the Imperial Army in the flesh. Investing far more in acting scenes than its predecessor on WWII, The First World War tells the story of Russia's war from the point of view of soldiers and junior officers as well as generals and senior commanders. We learn the biographies of many of these people, some of whom will go on to fight on opposite sides of the Russian Civil War—people like Brusilov, Wrangel, and Kornilov. We also learn of specific units—Cossack brigades, "steel divisions", national "volunteer units" and even partisans. A nice touch is the fact that all the actors speak the languages of the ethnicities and nationalities they represent, which is then translated. It's clunky, sure, but it beats the Western documentary penchant of having belligerents from all sides speak English in a British or American accent.

The humanity of these scenes is particularly poignant. There was plenty of suffering and horror in the East: chemical weapons, freezing cold temperatures and trench warfare. The poor state of equipment—the lack of warm clothing, artillery ammunition, and trained manpower—comes across in many a scene. Contrary to common myth, Russians are just as capable of freezing to death or dying of disease as anyone else—and at least 155,000 did just that.

The documentary also helps to put paid to one of the most enduring myths of WWI—and WWII, really—that of German invincibility and Russian ineptitude. Not every German battle against the Russian Army was a decisive victory like Tannenberg. When properly led, Russian units could and did make life hard for the Kaiser's army, even if it were not its equal. The time for a more balanced understanding of these two belligerents is long overdue, and The First World War is a good step in this direction.

Further archival and historical research will no doubt adjust or even correct many of the series' arguments. But one thing is certain—Russia's war is unknown no longer.

Lighting the Fire

So far, so good. But the documentary purports to cover the entire war, and this means discussing the background to WWI and the Western participation therein. This is where we get into trouble.

For a start, The First World War's coverage of the July Crisis is riddled with errors. Wilhelm II certainly bears a large share of blame for the war, but this documentary makes it sound like he was chafing at the bit to blow up Europe from the get-go when he was actually more cautious than that. Furthermore, no-one aware of recent scholarship would agree that Austria-Hungary was forced to attack Serbia by Germany; all available evidence suggests Austria-Hungary was out to crush Serbia whatever the consequences.

The series also claims that after Russia refused to call off its mobilization, Germany accidentally handed two official notes to the Russian government—one in the event Russia demobilized and the other in case it didn't; Both announced war against Russia. This is the first time I've heard of this, and even if the story is correct, it does not mean Russia was entirely innocent of responsibility for the outbreak of the war.

The key issue is the assassination of Franz Ferdinand which served as the spark for the conflict. We know that the man who organized the murder was Serbian Head of Military Intelligence, Dragutin "Apis" Dimitrijević. We also know that Russian officials in Serbia gave Apis backing and funding on a number of occasions. Balkan specialist Dr. John Schindler believes that Russian officials—either on local initiative or from up on high—gave Apis the green light to kill the Archduke.

I myself am agnostic on the matter, mostly because I don't trust a word that comes out of Dimitrijević's mouth. Even in the admittedly sympathetic biography by David Mackenzie, Dimitrijević's true nature comes out—a silver-tongued, ruthless sociopath who had no problem killing kings, conspiring against his own democratically-elected government and stabbing even his closest comrades in the back.

Dimitrijević "confessed" to his involvement in the assassination a number of times, each version contradicting the other as well as known facts about the case. Maybe he lied in his 1917 confession when he denied a key Russian official knew about the assassination but told the truth about Russian funding for the operation in the same document. But given his track record for truth telling, I prefer hard evidence from someone whose name is not Dragutin Dimitrijević.

But even if we give Russia the benefit of the doubt and assume they had no foreknowledge of the plot, they certainly knew who they were dealing with. At minimum, Russia's decision to back Dimitrijević was akin to the mob backing the Joker: they may not have known exactly what he would do, but they knew it would not lead to stability. Furthermore, they most certainly figured out the truth after the assassination. A responsible power would have done everything it could to throw a mad dog like Dimitrijević under the bus after Sarajevo. If a trial was too risky, less formal methods could have also worked.

In sum, Germany and Austria-Hungary bear the primary blame for turning an act of terrorism into a world war. No-one doubts that the Czar himself did not want war, although many Russian politicians and ministers did. But to claim Russia had no hand in the matter is simply untenable.

The Liberator of Nations or Their Jailor?

The next serious problem with The First World War's "official narrative" is its claim—usually made implicitly—that Russia not only did not want war, it also had no explicit war aims aside from liberating peoples from the oppressive grip of the Central Powers. The documentary shows scenes of the defection of an entire Czech unit from the Austro-Hungarian to the Russians (a known, but rare, event) as well as volunteer Caucasus and Armenian units who fought in the Russian Army. This as opposed to Germany, which bombarded peaceful cities, Ottoman Turkey which committed the Armenian Genocide, and Austria-Hungary which mistreated civilians in territories it occupied.

Since German and Turkish misdeeds are well known and debated, let me focus on the less familiar matter of Austria-Hungary. The facts themselves are not in serious dispute: Upon re-occupying Galicia and conquering Serbia in 1915, Austro-Hungarian military authorities, already overly and often unjustifiably suspicious of "suspect" ethnicities, conducted a campaign of repression which included many summary executions for minor offenses. The Austro-Hungarian army also interned tens of thousands of "unreliable" civilians in concentration camps in places like Talerhof and Terezin.

Dr. Jonathan Gumz vigorously—and in my view, rightly—disputes the idea that Austro-Hungarian behavior was nothing more than a training ground for Babi Yar and Buchenwald, but even he concedes the essential facts. No amount of righteous anger over the death of Franz Ferdinand or justified complaints about Serbian komitadji (Serbian guerrilla fighters) can change the fact that this was not the famously tolerant monarchy's finest hour.

But Russia's hands were just as dirty. Cossack troops in particular were famous for committing all kinds of "random" acts of violence, rape and murder, both during the Russian advance and retreat. The Russian policy of "scorching the earth" upon their retreat might have served them militarily, but it certainly did not help the civilians they abandoned.

As for "liberating" nations, anywhere the Russian Army advanced—in Galicia for example—it engaged in suppressing minorities such as the Ukrainians. Russia also expelled hundreds of thousands of Jews, Germans and Poles into the Russian interior as suspected enemies. Untold numbers died from hunger, exposure and disease. As for the Armenians, at least per scholar Dr. Peter Gatrell, the Russian government intended to settle Russians in newly conquered Eastern Anatolia rather than resettle the refugees from the genocide or give them any autonomy. Liberator of peoples, indeed.

Who Helped Who?

The coverage of the non-Russian fronts is also uneven. To be sure, viewers of The First World War will learn of aspects of the Western Front which don't always get mentioned, such as the participation of a Russian Expeditionary Force in France and its experiences, as well as British assistance to Russian naval fights against the Germans in the Gulf of Riga. The First World War is also surprisingly fair when it comes to fighting on the Western Front, seeing the Somme as the beginning of the end for Germany's position there after two years of false starts rather than a wasteful bloodbath for no purpose. The 1st of July, 1916 is put in the middle, not the beginning of the description of the Somme, and the French are given their rightful place in this pivotal battle.

But once again, nationalist bias creates problems which needn't be there. Anyone watching this documentary might get the impression that until 1916, the Russian Army effectively shouldered the burden of war alone while the Western allies were getting their act together. This is true up to a point, but The First World War goes too far on this matter.

For instance, it is true that the Russian invasion of East Prussia in August 1914 forced the German Army to detach forces from its attack on France. This likely helped the French and British defeat the Germans at the Marne. But it's not clear that the Germans would have won even with those forces, and surely the critical maneuver by the BEF into the gap between German armies was deserving of mention.

Maybe the best example of this misunderstanding is the year of 1915. The Russian Army did indeed bear the main offensive thrust of the German and Austro-Hungarian armies while the British and French armies were still figuring out how to break the trench stalemate. But given that the French suffered its highest number of annual deaths in the war trying to do so, and just by existing tied down substantial German forces, perhaps The First World War might want to be a tad kinder.

Where The First World War correctly highlights the Russian contribution to the war effort is in 1916. While this is the first time I've heard that the failed Lake Naroch offensive forced the German Army to pause their attack on Verdun, the famous Brusilov Offensive was of a different order of magnitude.

Put simply, General Alexei Brusilov was responsible for one of the most strategically significant offensives of the entire war. Using innovate tactics and methods, Brusilov broke the back of the Austro-Hungarian Army. The Central Powers' pressure on the Italian Army was relieved. Meanwhile, the French were able to revert to the offensive at Verdun, regaining territory as well as confidence in victory. German forces were tied down in the East who could not help stem the tide at the Somme. Although the other Russian commanders did not even try to follow up on Brusilov's success, such a breakthrough promised much for the future.

A Stab in the Back—And Freedom's to Blame?

All of which brings me to the most interesting yet maddening part of The First World War—the fateful year of 1917, the last episode in the series. According to this sad final chapter, Russia was on the brink of victory in 1917. The manpower was replenished, the equipment stocks were full, and the combat methods were more sophisticated. At the very least, the Austro-Hungarian Empire would finally fall apart, leaving Germany overwhelmed and isolated. All the sacrifices would finally be vindicated.

Then, suddenly, everything went wrong. In February, a chance shortage of bread in St. Petersburg led to rioting and then turned to revolution. Then, in an extraordinary act of disloyalty, members of the State Duma (the Russian parliament) conspired with the senior commanders of the Russian Army to convince Czar Nicholas II to abdicate in favor of a civilian government rather than do their duty and put down the rebellion. Nicholas reluctantly agreed.

The results were not long in coming: army morale collapsed, millions deserted and those that remained were barely willing to hold their positions let alone attack. Nationalities of all kinds strove for independence. The German Army went through them like a hot knife through butter at places like Riga. Eventually, the Bolsheviks—alternately accused of working for German intelligence or international finance—staged a coup d'etat. The Bolsheviks then proceeded to sign the humiliating treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which handed the most fertile and productive regions of Russia over to Germany. It was a humiliation not just of Russia but of the Czars, who had never been forced to concede conquered territory.

When I finished watching this, my jaw was on the floor. This was one of the most disingenuous acts of historical deceit I had seen in a long time—the perfect mixture of true facts mixed with innuendo, lies by omission and the hiding of critical context. If most works view the revolutions of 1917 as an inevitable event sped up by WWI, The First World War views it as nothing more than a freak accident. Per the producers, Russia did not suffer appreciably more in terms of lives, inflation or material discomfort than other parties to the conflict. Its soldiers were almost entirely loyal to the Czar and the Empire and the rear was mostly quiet.

What's even more troubling is that this narrative is literally one of Russia being "Stabbed in the Back" from the rear, much like the German legend fomented in 1918 which helped drive the Nazis to power a decade and half later. Lest people think I exaggerate, there is a scene in the final episode where an enthusiastic scout collects intelligence for a coming offensive in mid-1917, only to be stabbed in the rear by soldiers who have had enough and just want to go home. Subtle.

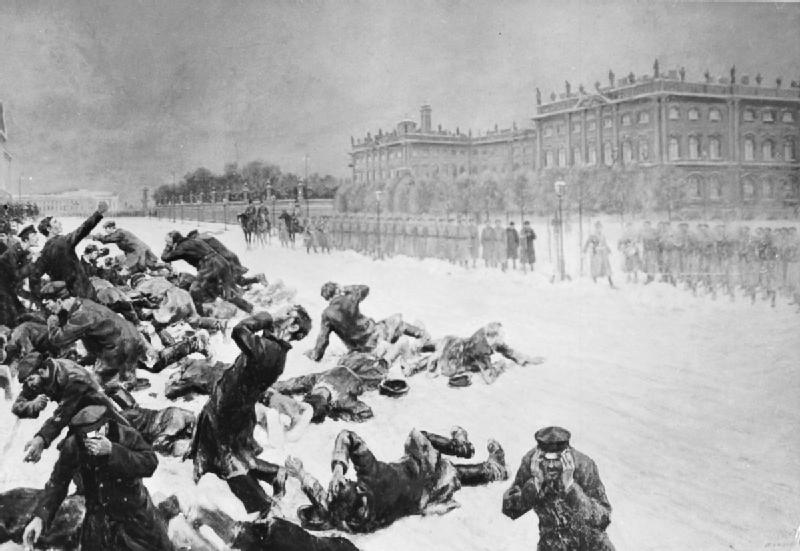

I refute this documentary's argument by mentioning a single year: 1905. No-one aware of Bloody Sunday, the Octobrist Manifesto, the Union of Unions and the massive national, rural and industrial revolt against Czarist oppression in that year can buy the idea that the Empire was entirely behind the Czar in 1917. If Russia society was a societal tinder box before 1905, afterwards it was a ticking atomic bomb, full of mutual class and societal hatreds.

Nor was 1917 disconnected from the war itself. While there were officers and generals like Brusilov who genuinely cared about their men—they were often the exception, not the rule. The infantry largely came from the poor peasantry, the officers from the gentry and aristocracy. The two hated each other: officers often berated their soldiers as scum or beat them for the slightest infraction or discourtesy.

The worst example was when officers addressed soldiers with the familiar Russian 'you', generally reserved for animals and children—the Russian equivalent of a Klansman calling a grown Black man 'boy'. For their part, the peasant soldiers got swift revenge after the revolution, killing or scaring off many of the self-same officers.

Many of the peasant soldiers had little idea of nationalism or duty beyond the duty of fear, the love of Czar having disappeared in 1905. After three years of hell on the Eastern Front, after massive defeats like Gorlice-Tarnow, mishandling and corruption by people like Rasputin, and their longing to go home to their land—most had had enough. There was a very good reason why all Nicholas' commanders recommended that he abdicate—no-one could guarantee that soldiers sent to crush the revolution would not join it. The military leaders were not leading the crowd, they were following it.

If Russian society did indeed tear itself apart after 1918 to horrific effect, the Czar and his court have themselves to blame, having stuck to the idea of direct and unfettered personal rule to the very end. Had the Czar allowed the genuine development of civil society and democratic freedoms, with the concomitant increase in public awareness and loyalty, things might have turned out differently or at least not been as violent. But one extreme led to another—despotism gave way to anarchy which then gave way to a far worse despotism than the first. While I commend the documentary's attempt to judge Russia's WWI separately from the revolution that followed, their revisionism goes too far.

But the real tragedy is the series' underlying message. For the people of The First World War, throwing the Czar out in 1917 was not just horrifically bad timing, but a fundamental betrayal by a bunch of unruly children incapable of freedom, responsibility or greatness without the firm and often arbitrary hand of a dictator—be they a Czar, Soviet Dictator or Russian President. I found myself wondering how much contempt the producers had for their own people to believe this, shaking my head in disbelief at the tragedy of it all.

Orlando Figes, the great historian of the Russian Revolution, ended his magnum opus with the warning that if Russia truly wished to heal, it would need to honestly face the ghosts about 1917. If this documentary is any indication, that day is still a long way off.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

I read a diplomatic history of how WWI began by a Hungarian historian, Kallantaj or Kollantay or somesuch name. He used the papers of Count Tisza, the prime minister of the kingdom of Hungary under the Habsburg Empire and a member of the Austrian cabinet. The Austrians were under strong German pressure to issue impossible ultimatums to Serbia that could not be accepted. Austria did so. This was done against the warnings of Count Tisza who counseled against pushing the Serbs into a corner. But Germany very clearly wanted war and the Austrians went along with that, with results that we all know. Thus Kallantaj.

So the Russian-Serbian provocation by killing the archduke remains minor compared to the German desire for war.