Far too much of the country is without proper law enforcement. This must change.

Mida is introducing a new, special segment for the post-election period · Over the next few weeks, we will publish an issue-specific policy proposal every Monday, containing detailed facts and concrete recommendations to the Israeli government · This week, Mida covers the all-important issue of state sovereignty

In his A Dictionary of Political Thought, Roger Scruton presents two aspects to the term sovereignty. The first is external—the recognition of the legal right of a political entity to a particular territory. The second is internal—the attributes of a political body towards a society under its control. Sovereignty in this sense is the supreme control of civil society, with both de jure (legal) and de facto (compulsory) aspects. In the present chapter we refer to sovereignty in the second sense: namely, law and its enforcement.

A democratic society needs the rule of law. Its citizens' lives and property require protection, free trade requires protection from theft, and public and national possessions need safeguarding. All of these are the most basic functions of a democratic government, without which freedom and prosperity are nothing but empty words.

In this crucial area of sovereignty, Israel is suffering a serious and continuous crisis. It has no systematic or thorough approach to enforcing law and order. Large sections of the state have become areas of anarchy where violence rules instead of law. Extensive territories in the Galilee, Negev and parts of the Sharon and Triangle area are effectively lawless. There is under-enforcement of building laws, no collection of taxes and worst of all—no serious protection of citizens' life and property.

Police Performance

The national police budget is less than 10 billion NIS, or about 2.9% of the state budget. The budget for the entire Ministry of Internal Security—including the prison and fire departments—presently stands at about 12 billion NIS or 3.9% of the state budget.

While this is a rate comparable to the OECD average, the manpower at the police force's disposal is not sufficient for its many tasks. According to a detailed analysis of the Israeli police done by McKinsey, Israel has 0.317 policemen per 1,000 residents on average, while the OECD average is 0.324 per 1,000 residents. This may be a fairly small gap, but when one considers that much of the police force is dedicated to fighting terrorism and related security threats—some 3,000 policemen belong to anti-terror units—the resources available to fight regular crime are effectively much lower.

When we go down to the local level, enormous gaps are often revealed: in Ashdod, there are only 164 policemen for a city of 250,000 residents—and only 70 of these are patrolmen. In Rishon Letzion, there are only 70 patrolmen and six patrol cars for a city with 350,000 residents. Holon, with 200,000 residents, doesn't even have its own police station.

Senior police officials have openly pointed this out. For instance, in 2012 then-Police Chief Danino explained in a discussion at the Knesset Committee of the Interior:

We need to remember that in the last two decades, the Israeli Police has almost not grown in real terms. When you look at what happened to the country in the past two decades—new towns have been established, there are cities that have almost doubled in size.

The police argue that there's been a significant drop in crime rates over the past few years, but when one conducts an international comparison, it turns out that at least when it comes to some crimes, the situation in Israel is far from satisfactory. Because of differences in reporting and recording of crimes, we can only do such a comparison for two types of crimes: home burglaries and car break-ins. According to the Crime Victims Survey conducted by the police (page 55), while the situation regarding car break-ins is pretty good in Israel, when it comes to home burglaries, fully 7.8% of the population has fallen victim, as opposed to the OECD average of 1.8%. Furthermore, the rate of these types of crimes is on the rise in Israel, while it is on the decline in OECD countries.

It's no surprise, then, that the public doesn't think the police is doing its job well. According to the police's own data, there has been a significant decline in the number of civilians who give the police high marks for performance: from 63% in 2002 to just 35% ten years later. The number of Jewish citizens who have faith in the police has gone down from an already low number of 36% in 2003 to just 21% ten years later.

These statistics match data regarding the reporting of crimes: the Crime Victims Survey conducted by the police reveals that Israel is below the OECD average when it comes to crime reportage: Israel has a 46% reportage rate compared to 51% on average in the OECD.

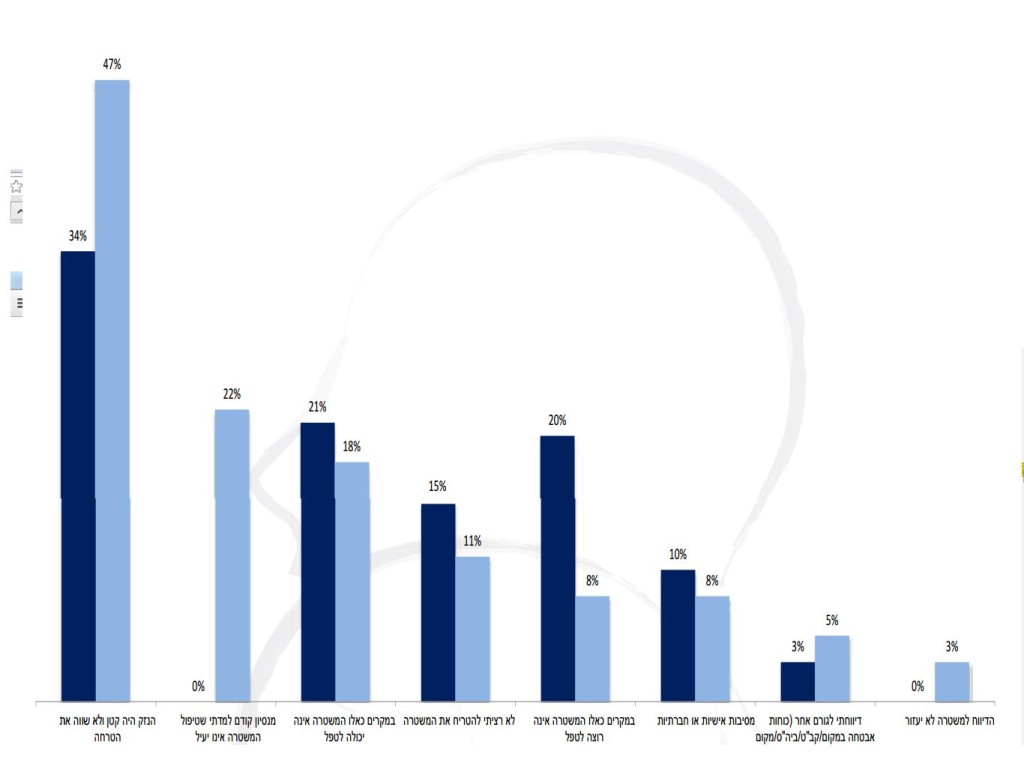

Why do most Israelis avoid reporting crimes to the police?

Well, here's the real problem: a quarter of those who reported home burglaries said that "from past experience, police handling was inefficient" and that "reporting to the police won't help." These are unprecedented numbers on a global level: Israel is the only OECD country to choose this answer as an option. Per the OECD average, many argued that the damage was too small (34%), others said they didn't want to trouble the police (15%) and that the police either doesn't want (20%) or is unable (21%) to help. But the Israeli feeling of fatalism and helplessness is unique: the number of OECD residents who responded like Israelis is one big zero.

As we stated, because of differences in reporting and recording of crimes between Israel and Western countries, this data is only partial. It might be that things are better when it comes to other crimes. But as the only two indications we have for an international comparison, this data is very troubling.

Therefore, in order to deal with these challenges, the government must significantly increase its investment in policing: more police stations, more patrol cars and most importantly, more beat cops. This is a sine qua non for restoring law and order in Israel.

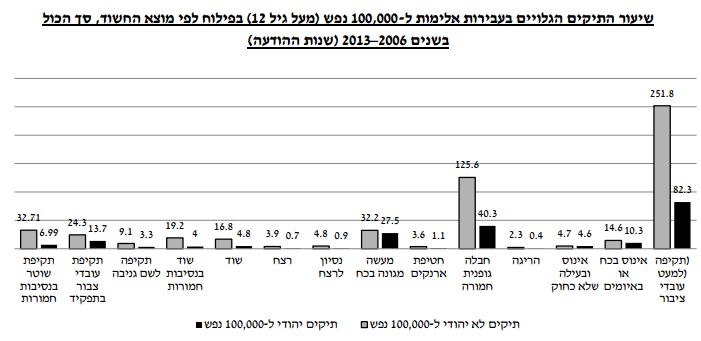

Crime in the Arab Sector

The situation regarding Arab crime is extremely severe. According to a report published by the Knesset Research and Information Center in 2014, fully 49% of criminals in prison are from the Arab sector, which is only 20% of the population. We're talking particularly severe crimes here: Arabs are 55% of murder suspects, 55% of attempted murder suspects and 58% of assault and battery suspects. This overrepresentation holds for those convicted of such crimes as well.

This data only represents crimes and assaults that were carried out. One can begin to understand the true nature of the potential danger when we examine charges for illegal gun possession in the Arab sector: between 2006-2013, more than 11,000 case files were opened for such crimes—and these are just the cases the police knows about. According to estimates, in the northern villages and elsewhere, there are thousands of illegal guns and stockpiles of ammunition.

The main victims of this lack of law enforcement are the Israeli Arabs themselves. According to the 2014 'National Violence Index' conducted by the Ministry of Internal Security, which examined violence in both Jewish and non-Jewish sectors, revealed that "in most cases, both the perpetrator and the victim are from the same sector." So, most of the victims of Arab criminality are other Arabs, who suffer from the lack of law enforcement and relevant norms of respect for the law.

What can we do to help the sector and the State of Israel as a whole?

Law enforcement models around the world have proven that when petty crimes are handled seriously, serious crime has difficulty taking hold. The State must invest in aggressively and effectively enforcing the law in the Arab sector. This means going into the villages and towns and enforcing the law in its entirety—from small-scale matters like traffic laws and business licensing, to polygamy and domestic violence, and up to and including a relentless war against violent crime. The state needs to rewrite the rules on the ground: a stubborn and unrelenting fight against the drug gangs in the Negev, operations to collect illegal weapons, and consistent actions against illegal construction.

We must not wait for the outbreak of nationalist riots and violence, which is sure to come if we continue to neglect the enforcement of sovereignty in the Arab sector. Steps taken in recent years in the Negev unequivocally prove the effectiveness of this method: in the wake of stringent enforcement of the law, fully half of illegal buildings which received a demolition order were destroyed by the owners themselves, even before the bulldozers arrived.

We must not discriminate against the Arab sector by failing to provide it with the basic services of law enforcement. We must invest the necessary resources to ensure the proper enforcement of law and order everywhere in the country. Such a policy will benefit the personal security of all Israel's citizens, and primarily—the Arabs themselves.

Lands

The total land area of the State of Israel, not including Judea and Samaria, is 20 million dunams. Of these, only 2 million dunams is allocated to construction. The rest is assigned to agriculture, nature preserves and firing ranges.

Of the land assigned to construction, the Jewish sector, including the mixed cities, has 525,043 km2 for housing construction. The Arab sector, not including the mixed cities, has 86,079 km2 for the same purpose.

While the Jewish Sector tends to high-density construction, the Arab sector, partially due to the lack of enforcement of building laws, tends to build in a spread-out, low-density manner. This is readily apparent in the population density statistics: in the Jewish sector, there are 11.13 people per km2 of housing, whereas in the Arab sector, this number is 9.06 per km2.

We should note that this data is based on the official jurisdictional boundaries set by the state; it does not include lands illegally seized and squatted on. Because of their tendency to build in a low density manner, Arabs complain of a lack of land, thus justifying this squatting phenomenon. We don't have exact data on illegal construction, but according to the broad estimates of authorities, there are some 70,000 illegal buildings in the north, with about 3,000 illegal construction projects started each year. The situation is worse in the Negev: some 85,000 buildings are spread out over 20,000 dunams. Here, too, there are 1,500 new illegal construction projects started annualy.

The situation, then, is getting worse on a daily basis.

The solution here is just as obvious. To change this trend, Israel must vigorously and systematically enforce building laws regardless of sector, location or the type of land takeover. Israel must make every effort to move people living in illegal concentrations and move them to organized and recognized villages, where they can get all the necessary infrastructure and services.

The facts are on our side. The establishment of a special Negev policing unit to deal with illegal construction in the Negev, alongside an effective policy of prosecution, has led to a significant increase in demolitions: 697 illegal buildings were destroyed in 2013 as opposed to just 369 the year before, with 376 buildings being destroyed independently by the owners themselves.

So, accumulated experience shows that a proper combination of strict enforcement, economic sanctions and appropriate alternative solutions leads to a significant increase in obedience to the law. These methods are feasible and are guaranteed to ensure significant improvement on the ground.

Infiltrations

The State of Israel has in recent years experienced a flood of illegal infiltrators, most of whom come from African countries. Although Israel has avoided conducting an organized check of their claims to be refugees, data collected over the years shows that most of them are not people fleeing for their lives from death or torture. Even the few who fled from genuine war zones, such as some of the refugees from Sudan, found refuge in some of the waystation countries they entered such as Egypt.

Of the 58,000 illegal infiltrators who entered Israel via the Egyptian border, almost all were men of working age. A study published by the Israel Prison Service showed that over 80% of infiltrators were men over the age of 18. The significance is clear: most of these people are not "refugees" but "work migrants."

There is no unequivocal data regarding the involvement of infiltrators in crime. The reason is that official data only relates to "reported crimes" which involve a complaint to the police. Naturally enough, crimes are not reported by members of the infiltrators' community, and there is a degree of under-reporting in cases where there is insufficient information to identify the perpetrator. Despite these limitations, recent data published by the police show an increase in crime among the population of African infiltrators, an indication of the social costs of this illegal immigration.

Worse, when it comes to serious crime, the police attest that infiltrators have a higher crime rate than their proportion of the population. As Commander David Guez, commander of the Yiftah district, testified:

The more we break down the violent crimes, the sexual assaults, the violent robberies, [the infiltrators'] share is much larger and more dramatic. If I just take 2012…their involvement in robbery incidents we know of and deal with has passed the 60% point of crimes we deal with in that designated area…acts of violent theft with a knife, an electric taser, tear gas or blows, or with a gang…incidents of forced rape and sodomy, their involvement has long passed the 60% rate.

Despite the partial data, a study we conducted showed that even based on the existing data and on the most cautious assumptions, the relative proportion of infiltrators in criminal acts in 2009 was higher than their relative proportion in the population, contrary to arguments we often hear.

Beyond the raw numbers and statistics, the reality is that the entry of infiltrators to neighborhoods in southern Tel Aviv and other areas has made the life of veteran residents a nightmare. Elderly people locked up in their homes, streets that are death traps and entire neighborhoods that have dramatically changed overnight. This illegal population has become a burden on the welfare, education and infrastructure services and caused entire areas to quickly deteriorate. This situation is a huge warning sign of the serious dangers of illegal infiltration.

The infiltration issue places a dual obligation on the state. On the one hand, the state must deal with the criminal hothouses and drop in personal security caused by the illegal infiltrators already here, and on the other hand, effectively secure the border to prevent further infiltration in the present and future.

Experience shows that it is possible to close the breach in the border. Until 2009, the IDF had a procedure of immediately returning infiltrators to the Egyptian side upon capture. This procedure had only limited effect, and over the years, infiltrators made it into Israel in growing numbers. But limited effectiveness is better than nothing. When the procedure was abolished in the wake of a Supreme Court appeal by the Israeli Civil Rights Union, the infiltration rate tripled to 17,000 in 2011 alone.

The use of other methods has also proven itself: building an Egyptian border fence, alongside the enactment of the Infiltrators' Law which significantly constrained the employment conditions of illegal infiltrators made illegal immigration to Israel much less worthwhile. The fence, which was finished in 2012, led to the almost complete cessation of infiltration (only 117 people infiltrated in 2013). The Infiltrators Law led to the voluntary departure of some 9,000 infiltrators in 2013-4, a number unprecedented compared to Europe which is struggling with a similar problem.

We need to continue with these methods: increase control of the border alongside creating a system of incentives that will encourage departure and discourage further infiltration. We need to make the conditions of residence in Israel harder, make access to the welfare system more difficult, and make it more difficult to achieve permanent resident status. A proper combination of these can lead to a strategic sea change.

English translation by Avi Woolf.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.