Israel needs to find a balance between changing an unstable system and avoiding unintended negative consequences.

Like many things when it comes to human behavior, changes in way the country runs could lead to unexpected and undesirable results · In the State of Israel, where a government changes about every two years, one needs to be especially careful lest reforms are passed which can only cause harm · Still, there are some changes which can do some good

Israel's system of governance does not allow for a stable government or governance in general. It's true that it allows expression for all segments of Israeli society but—as we've seen recently—it also prevents taking decisive action. Instead, any coalition is made up of disparate parties with often conflicting agendas. The system grants a great deal of power to small or middling parties, especially sectorial ones whose demands, justifiably or not, are seen by most of the public as blackmail.

In addition, the present system condemns the State of Israel to perpetual instability. The 34th government in Israel's history was sworn in on May 14, 2015—34 in 67 years. On average, a government every two. Elections have not taken place on time since November 1988, and there is no reason to think they will take place on time next time, either.

The road to governance is paved with good intentions

Now everyone will ask: So what do you suggest? What's the alternative?

Over the years, the Israeli government has tried to pass reforms to "strengthen governance", but the result was often the opposite. For instance, the law to directly elect the Prime Minister, passed in 1992, was supposed to reduce the power of small sectorial parties and strengthen the executive. In practice, it helped the large parties disintegrate: in 1981, the two largest parties of Labor and Likud won 95 out of 120 seats—almost 80%, in 2015, they won only 54 seats or 45%. Ever since 1999, the two largest parties combined do not have a majority in the Knesset, so even a "unity government" doesn't mean anything anymore.

Another attempt to deal with the situation was raising the voting threshold, in the belief that this will weaken small parties and strengthen large ones. But the small parties merely merged and even became stronger—see, for instance, the Joint Arab List. Congrats to Lieberman.

The main conclusion from all these failures is that we need to be particularly careful in any future reform and seriously consider all the possible consequences stemming therefrom.

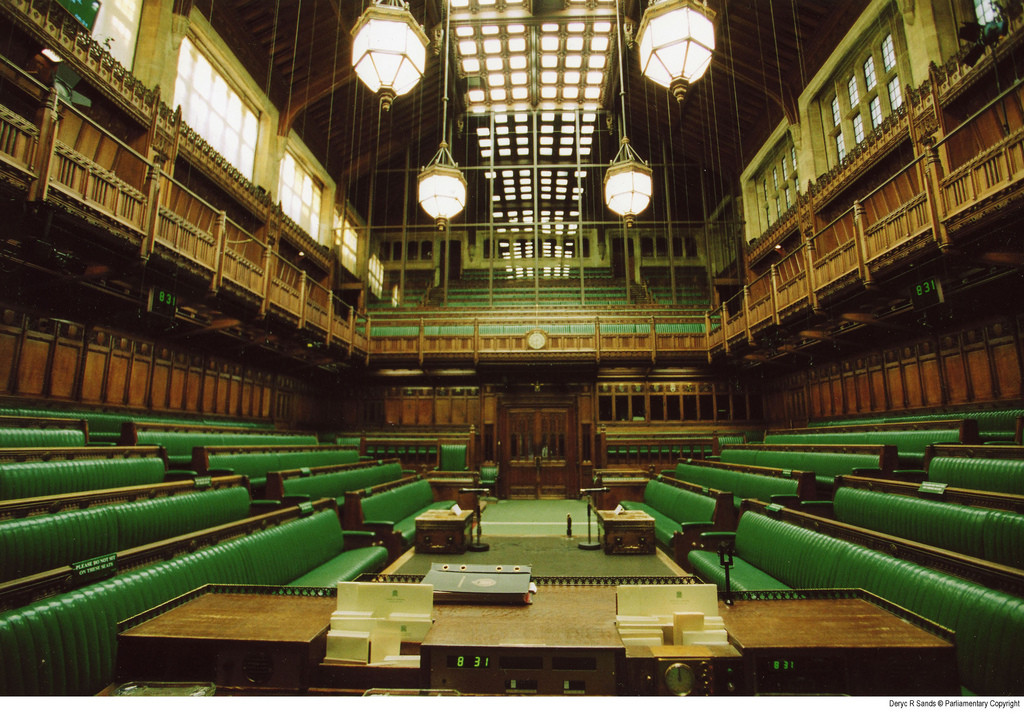

A reform in the electoral system needs to retain the delicate balance between representing the public and democratic majority decision. Representation has become something of a fetish in Israel, and there is no doubt that it needs to be changed. There is almost no democracy in the world where parties receive parliament seats perfectly equivalent to the number of votes they receive. In most, the victors get a premium or bonus. In the recent elections in Britain, for instance, the Conservative Party won 36% of the votes but gained 51% of the parliament seats. This gap leads to a clear victory and allows the elected government to function properly.

The majority decides?

The most efficient method for achieving a clear decision is first-past-the-post, in which the Prime Minister is the leader of the party which received the most votes. This system is usually based on a system of districts, each of which chooses one representative for parliament. In Europe, there are two methods to implement this: the English system and the French system.

In the English system, elections have one round, and party which received the majority of votes, regardless of how many, is elected. This system clearly encourages a two-party system. Indeed, up until a few decades ago, the two largest parties won about 96% of the parliament seats. But the disintegration of party politics that has been the lot of the Western world has not skipped over Britain, and in the recent elections, the two largest parties only won about two-thirds of the seats in parliament—still impressive in Israeli terms. Despite this, thanks to a system which requires winning a majority in each individual district, the Conservatives won an absolute majority, and they can rule without coalition partners.

The French model contains a small but significant variant on the English one: elections take place in two rounds, and only a party which reached a certain threshold—in this case 12.5% of the vote—can make it to the second round. This system allows a wide expression to a variety of opinions and ideologies in the first round, and encourages alliances among parties for the second. In practice, the two largest parties, the socialist and the right-wing one—which changes its name every few years—succeed in always winning a clear, solid majority. In 1993, the right-wing party even won 80% of parliament seats with 40% of the votes.

Should Israel adopt such a system? It's not so clear. The first-past-the-post system has a number of clear deficiencies, the most prominent of which is that representation is sacrificed for the sake of a clear outcome. Some communities are punished with underrepresentation in parliament while others are overrepresented. For instance, while the UKIP party received no less than 13% of the vote in Britain, it has only one parliament seat out of 650. Less than 0.2%! The same is true in France: the National Front party won 14% of the votes in the 2012 elections, but only two seats out of 577. By contrast, the Scottish National Party won only 5% of the votes, but got 9% of the parliament seats.

So what's going on? Because of the division into districts, the system favors powerful local groups and harms national movements whose support is spread evenly throughout the country.

What's Good for Israel?

In tribal Israel, different sectors tend to live in separate towns and areas. There are Arab and Haredi cities where the winning side in a local election isn't open to doubt. So, the first-past-the-post system may weaken sectorial parties, but it will not eliminate them. As part of the Law of Unintended Consequences, it may even strengthen the "family" nature of many local governments and cause additional problems.

But that's just the beginning. In a district system, the question is how you divide the districts. The city of Bnei Brak, for instance, is worth about 3 Knesset seats. The city could be divided into three districts which are all guaranteed to elect a Haredi representative. Or we could ignore the municipal boundaries and attach Bnei Brak districts to adjacent cities in such a way that no Haredi representative will win. This is known in the US as gerrymandering—deliberately fixing district boundaries to fix elections—and it is a recipe for disaster and violent protest.

Of course, we don't have to go completely over to first-past-the-post. Some have suggested a limited degree of this system within a system of proportional representation, so that between a quarter and a half of representatives will be elected with first-past-the-post while the rest will be elected via proportional representation. The main advantage in this system is creating large districts which will neutralize local power brokers. On the other hand, it isn't clear how this will help ensure a clear and stable parliamentary majority.

Based on the 2015 election results, for instance, assuming half the MKs will be elected through first-past-the-post, for the Likud to win, they must win 46 out of 60 seats. It's possible, but doubtful. In addition, there would form two classes of MKs with different levels of legitimacy—MKs elected directly by their local constituents and those elected based on their party in national ones. The former will enjoy greater legitimacy, with results which may be negative.

There are other proposals for strengthening Israeli governance and government stability without going to first-past-the-post. Binyamin Netanyahu tried to promote a law which would automatically give the job of forming a coalition to the largest party. But it's not clear that this would help: Likud won the largest number of seats (30), but the task of forming a coalition was still a huge headache. In 2009, Kadima technically won the most seats, but it had no chance of making a coalition, and the job was given to Netanyahu. Even under Netanyahu's system, Livni would get the job to form a coalition, fail, and Netanyahu would then get it. Nothing would change except six weeks would be wasted.

So what can we do?

We need to be very careful when changing the rules of the game. There are always unexpected results. Perhaps we could try Netanyahu's suggestion with a twist: the elections will be for the first 100 seats in the Knesset, and the largest party will be awarded the remaining 20. This is a significant addition to the winner and under such a system, the public will prefer voting for likely winners, as the "blocs" would become meaningless. Such a change will be an incentive to parties to unite and will create two large parties which can easily run the country. And the Land would be at peace—at least for four years.

English translation by Avi Woolf.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

Why not simply abolish lists and have voting districts so that all elected officials represent an actual local consituency?

Why not be a trusteeship and another state of the USA.