For the Jews, the fight against the Russian Army in Galicia in WWI was far from "futile" or "pointless".

Contrary to its later Anglo-dominated image as a war for no purpose, most of those who went to war in 1914 felt they were fighting on the side of justice and right • This was especially true of the Jews of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, who saw the fight against Czarist Russia as one against barbaric anti-Semitism and pogromist violence • A look at the "personal" motives of one of the many peoples who fought in the Great War

The soldiers who went to war in 1914 did so for a variety of often conflicting reasons, and nowhere was this truer than in the multi-national and multi-confessional Austro-Hungarian Empire. Some did so out of loyalty to the Dual Monarchy, a concept well understood in 1914 but foreign to us in the 21st century. Others genuinely wished to avenge the death of Franz Ferdinand and crush Serbia, and all the Empire rallied to crush perfidious Italy when it entered the war on the side of the Entente in 1915.

For the Jews, however, the main enemy was unquestionably Czarist Russia. While many of the Dual Monarchy's Slavic subjects – Czechs and Ukrainians chief among them – were not enthusiastic about fighting a fellow Slav power, Jews felt the opposite. Russia was for them the epitome of barbarism: the most unapologetically anti-Semitic regime on earth, held responsible for murderous pogroms at Kishinev, Odessa and elsewhere, to say nothing of the many restrictions the Russians placed on Jewish movement, residence and rights.

As Marsha Rozenblit shows in her masterful study on Austro-Hungarian Jewry during the Great War, Austro-Hungarian Jews of all stripes were enthusiastically anti-Russian in a way they weren't against any other enemy of the Monarchy. Jewish officers and soldiers – some 300,000 fought on the Monarchy's side – were the most gung-ho when they fought the Russians. Rabbis and leaders openly referred to Russia as a group of barbaric Cossacks, a "kingdom of darkness" of rape, robbery and brutality against the enlightened and civilized Empires of Germany and Austria-Hungary. Rabbis openly declared the war against Russia a "holy war", comparing Russia to the Jewish People's most hated enemy since Biblical times – Amalek.

Amalek's chosen ground was Galicia.

Galicia: The Forgotten Battlefront

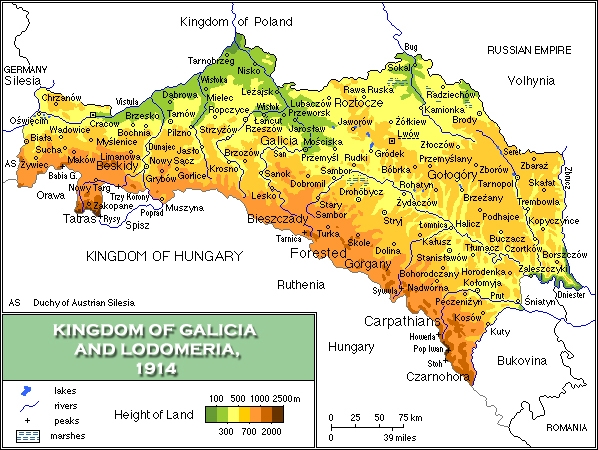

Galicia is the ultimate forgotten battlefront of the First World War. Soldiers fought over places that are either unpronounceable or forgotten – places like Przemysl, Lemberg and the Carpathian mountains. Most of its soldiers were illiterate or at least wrote in poems largely untranslated into English; the English-speaking world does not really know of an Austrian, Czech or Russian Wilfred Owen or Rupert Brooke. Jaroslav Hasek and Stefan Zweig cover some, but not all, of the enormity of this experience.

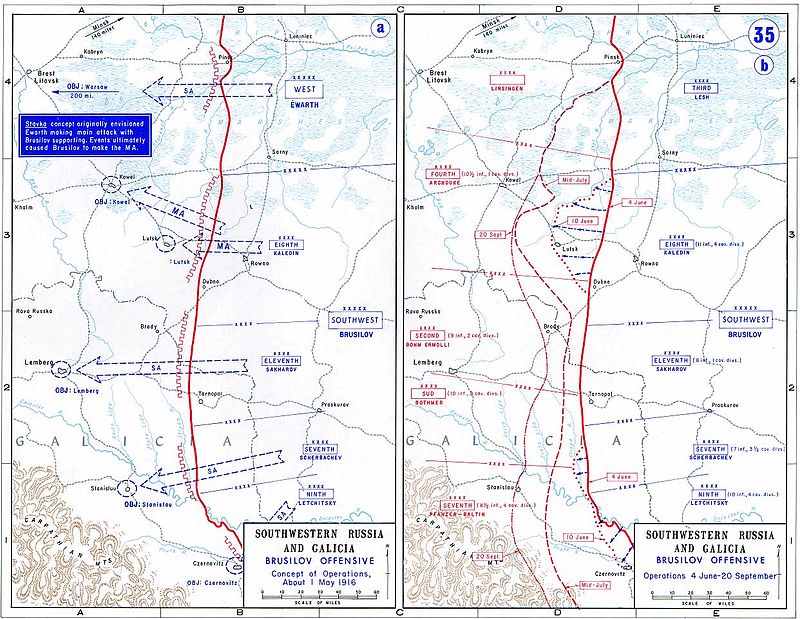

It was also, relatively speaking, a bloodier front than in the West. In the four month Brusilov offensives, for instance, some two million Russian, German and Austro-Hungarian soldiers were killed, wounded or captured. That's about the same or slightly more than the "big battles" of Verdun and the Somme combined. Remove the critical year of 1918, when the Russians were taken out of the war and now focused on killing each other, and there was more human suffering in the fields of Galicia than in those of France and Flanders.

In 1914 and the beginning of 1915, the Russians had the upper hand, conquering Lemberg, reaching the Carpathian mountains and crushing the Austro-Hungarian Army. Then the Germans counterattacked, breaking through and driving Russian armies ever eastward in what became known in Russia as the Great Retreat of 1915. The Russians then counterattacked in 1916 in the famous Brusilov Offensive, whose innovative tactics even inspired German tactics of later operations.

Refugees and Solidarity

This seesaw of movement was a recurring nightmare for the civilian population, especially the largely traditional and Hassidic Jews who lived in the region. Already living in the most impoverished region in the Empire, they had everything to fear from the front coming near even beyond the general destruction of the war. Whenever the Russians arrived, they immediately mistreated the Jews first and foremost; during the Great Retreat of 1915, Russian armies expelled 400,000 Jews into the interior of the empire as spies and German and Austrian sympathizers.

It's no surprise then, that almost half of those who fled the Russian steamroller in 1914 into the Monarchy's interior were Jews. Jews fled to areas such as Bohemia and Moravia, and most of all, big cities such as Prague and Vienna. In contrast to German Jews, whose attitude towards their Eastern and traditional brethren was often mixed with contempt, Vienna Jews especially welcomed these refugees with open arms. It helped that many of the Jews in Vienna were often descended from Galicianers themselves, and so were more familiar and less alienated by these strange looking Jews with their caftans and beards.

The influx of Jewish refugees, which remained between 100,000 to 200,000 over the course of the war, strained Jewish resources, but also led to a heightened sense of solidarity among Austria-Hungary's Jews. With the help of tolerant officialdom, Jewish communal organizations helped to maintain these refugees, most of whom were women, children and the elderly – most of the working age men fighting in the army or having been expelled by the Russians.

Increased Jewish solidarity

The plight of the refugees not only strengthened the Jews' hatred of Russia and support for Austria-Hungary as their shield and savior, they also strengthened Jewish solidarity. Unlike in Germany or France, where Jews had to identify nationally with the majority nation, Jews in the supranational Monarchy could easily identify as a separate nation or people without casting doubt on their loyalty to the non-national Monarchy. Thus they could openly speak of Jewish fighters and the suffering of specifically Jewish refugees, at least in the first years of the war, without being accused as virulently of double loyalty or the like.

Indeed, one of the most tragic aspects of the Austro-Hungarian Jewry was that they ended up remaining staunch defenders of the Monarchy long after most other nationalities were abandoning it and clamoring for greater political autonomy and independence. These were not politically tolerant national movements, either, but overtly ethnocentric and xenophobic majoritarian movements who had little use for either Jews or other minorities in their midst. The Jews had seen the successful defeat of the anti-Semitic Russian Empire in 1918, only to confront growing Jew hatred in their own backyard, complete with pogroms and reduced rights.

But that is a story for another time.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

קריאה שנתנה לי זווית מעניינת על מלחמת העולם הראשונה, תודה!

Recently a comprehensive exhibition was opened in Vienna on the Jewish participation in WW1. I have reported in detail about the exhibition: http://riowang.com/2014/04/doomsday-in-vienna.html, and soon I will also write a review about its catalog.