Scottish independence may happen on Friday. Stephen Daisley explains what this will mean for Scotland, Britain and Israel.

Long a fringe phenomenon, Scottish independence might become a reality this Friday • How did this happen? • Was it because of Scottish nationalism or economics? • What will independence mean for Britain and the West? • And what are the ramifications for Israel? • Stephen Daisley, referendum reporter for Scotland's leading commercial broadcaster, explains

Close your eyes and picture Scotland. What do you see? Rolling hills and glens? Highland cows and bagpipes? Shortbread and the Loch Ness Monster? Perhaps Mel Gibson in the days before his name was associated with drunken anti-Semitic jeremiads, when he was the Hollywood incarnation of Scotland’s semi-mythical warrior William Wallace?

These national symbols of Scotland’s history and culture are important – both to Scots and to our tourism industry – but they do not tell the whole picture.

What if I told you that Scotland is an oil-rich nation, the Saudi Arabia of north-western Europe, with somewhere between 16 billion and 25 billion barrels of recoverable oil in the North Sea (depending on which expert you turn to)? What if I told you that Scotland has a GDP of £130 billion, or £148 billion with a geographic share of those oil revenues included? What if I said the Clyde, on the West coast of the country, is home to the United Kingdom’s Trident nuclear deterrent system?

As part of the United Kingdom, Scotland has a seat on the United Nations Security Council and is a member of the European Union, allowing it to export goods worth £11 billion to the other 26 member states of the community. Thanks to the UK’s standing in international markets, Scotland can trade at a level that most small nations dream of. Its whisky exports are worth more than £4 billion while its tourism industry boosts the national economy by £10 billion.

This might sound like the recipe for a happy nation but Scotland is racked by discontent. On Thursday, the country goes to the polls in a referendum on leaving the United Kingdom and becoming an independent country. If the electorate votes Yes, and the polls suggest that this could happen, it will be the end of Scotland’s 300-year partnership with England, as well as Wales and Northern Ireland. The Union which enabled Britannia to rule the waves and the British Empire to control a third of the globe at its peak would be broken up.

Although the UK’s place in the world has steadily declined since the end of the Second World War, with brief upsurges during the Thatcher and Blair years, the country’s fundamental transformation if Scotland were to leave should not be underestimated. A country known for its stiff-upper-lip and cautious traditionalism would enter a period of constitutional crisis, embroiled in negotiations with a departing Scotland and forced to redraw its own governmental map to ensure no other partner-nation followed the Scots to the exit.

Unraveling the mystery

Why, then, given its economic health and the possible consequences of independence, could Scotland be about to quit the United Kingdom?

There are a number of answers, the first amongst them is institutional and takes us back to the pre-war period. The Scottish National Party was founded in 1934 to campaign for Scotland to become independent from the United Kingdom, a Union forged in 1707 when the kingdoms of Scotland and England were merged in the Acts of Union. The Nationalists argued that this alliance did not serve Scotland’s interests and in fact smothered the once-proud nation’s culture and identity. The SNP remained on the fringes of Scottish and wider UK politics for decades, edged out by the left-right rivalry of the Labour and Conservative parties and its own ideological vicissitudes. From time to time, it would shock the Westminster establishment by winning a by-election during periods of discontent with the Labour Party, the party which dominated Scottish politics for the second half of the 20th century, but it tended to lose these seats at the next general election.

But the Nationalists saw their opportunity in the rise of Margaret Thatcher, whose free-market economic and social policies sat at odds with Scotland’s vision of itself as a fair-minded and progressive nation. (Ironically, the SNP had helped Thatcher into power by voting with her Conservative Party to bring down the Labour government in 1979.) Throughout the 1980s, Scotland voted Labour but found itself governed by successive Thatcher administrations and subject to unpopular industrial and taxation policies. As Labour moved to the political centre, the Nationalists repositioned themselves as a left-wing party and used Thatcher’s unpopularity to lobby for independence.

The landslide election which brought Tony Blair to power in 1997 also saw a referendum in which Scotland voted to create a Scottish Parliament. This legislature, based in Edinburgh, was put in charge of Scotland’s economy, health, education, and justice portfolios while powers over defence, foreign affairs, welfare, and the bulk of taxation were reserved to the UK Parliament in Westminster. Devolution, as this new arrangement was known, was intended to “kill nationalism stone dead” in the words of one senior Labour politician. However, as the voters grew dissatisfied with Labour they turned to the SNP, and its charismatic leader Alex Salmond, and after narrowly winning the 2007 Scottish election the Nationalists formed a minority government. Although the Scottish Parliament’s electoral system was designed to encourage coalitions, the SNP set off a political earthquake when it went on to take majority control in the 2011 elections.

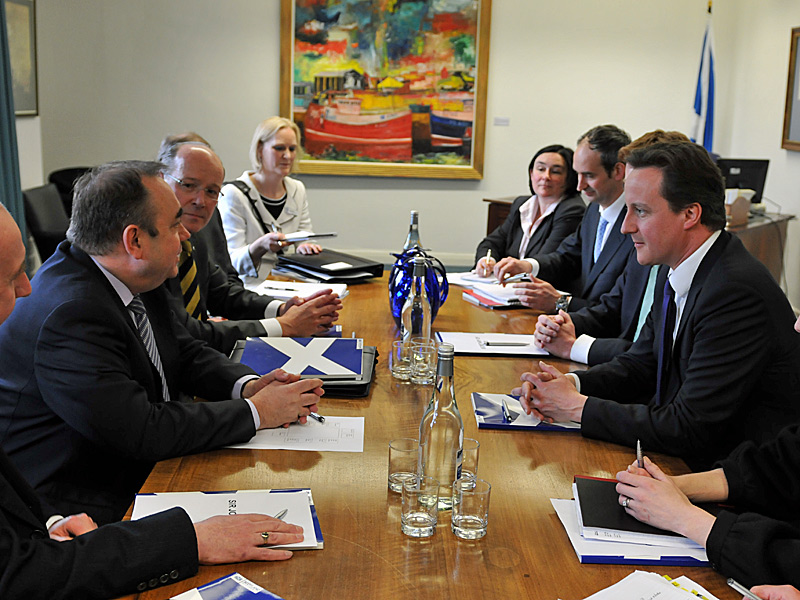

Mr Salmond used his mandate from the voters to pressure the UK Government into holding a referendum on Scottish independence. When Prime Minister David Cameron agreed to allow the plebiscite, it was close to unthinkable that the Nationalists could win the vote, with only one-third of Scots supporting a breakaway from the UK. However, Mr Salmond, a sharp political strategist, recognised that nationalism alone could not deliver a majority for independence. For that, he would need to turn to economics.

This isn't Adam Smith's Scotland

The economy of the UK and Scotland, and the divide between rich and poor, constitute the second answer to our independence conundrum. While Scotland is known around the world as the birthplace of liberal economist Adam Smith, Scots progressively abandoned free market principles and by the mid-20th century state-engineered equality had cemented itself as the nation’s central political ethic. Socialism has since given way to redistributivist capitalism but Scotland’s self-image as an egalitarian society endures. “We’re a’ Jock Tamson’s bairns” goes an old Scots saying: We’re all the same. That egalitarian impulse is prominent in the referendum, with the Yes campaign framing independence as the opportunity to realise a more “socially just” society.

Yes campaigners point to income inequality and poverty as evidence of the failures of the UK economy. The standard measure of income equality, the Gini coefficient, assigns the UK a rating of 0.345 after taxes and transfers, placing Britain 28 out of 34 OECD nations. Only countries like the United States, Israel, and Turkey are less equal. The expansion of food banks has been a hot-button issue in the campaign, with pro-independence activists arguing that such charities are a symbol of a Westminster-dominated political system that favours the wealthy over the needy. The Nationalists have also seized on statistics suggesting one in five Scots, including 200,000 children, are living in “relative poverty” as proof that the welfare reforms of the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government at Westminster are hurting the poor.

Nicola Sturgeon, Deputy First Minister of the Scottish Government and figurehead of the Left within the SNP, argues: "It is vital that we gain the full powers of independence in order to build a better Scotland – one that protects people from poverty and helps them fulfill their potential in work and life."

That is why political issues like economics, welfare, and “social justice” – rather than constitutional questions about the structure of government — have led the agenda in Scotland’s referendum. The Nationalists calculate that, if they can appeal to disaffected Labour voters, they can construct a majority for independence. Their opponents in the No campaign, however, point out that the SNP has failed to outline any tax policies to achieve its social democratic ambitions while encouraging enterprise and productivity.

Much of the No campaign’s efforts have been focussed on talking about the consequences of Scotland going it alone. How, they ask, would Scotland afford its generous welfare state, socialised healthcare, and free university tuition? What would happen to the economy when the oil revenues dried up? What currency would an independent Scotland use and would it be granted membership of the European Union? This risk-raising strategy, known as “Project Fear”, has backfired on the No campaign, depleting their substantial poll lead as voters become more sceptical about independence warnings.

With the polls neck-and-neck, the parties which make up the anti-independence “Better Together” campaign have promised more powers for Scotland short of independence. They hope that this offer will convince Scots that they can have “the best of both worlds”: An even stronger Scottish Parliament backed up by the strength and security that comes from being part of the UK.

Small country, worldwide repercussions

Foreign policy has played a remarkably muted role in the referendum. After the failures of Iraq and Afghanistan, there is little appetite for an independent Scotland to take as active a role in world affairs at the UK Government currently does. A central plank of the Nationalists’ platform, however, is the removal of the Trident nuclear defence system from Scotland in the event of independence. This poses a significant challenge to the UK Government – which says it has no other base where the nuclear submarines can be docked – and could see the future of the British nuclear arsenal thrown into doubt. In this scenario, the United States would see one of its closest allies unilaterally disarmed and the divisive subject of nuclear weapons would be on the international agenda at a time when the West is trying to unite against the Islamic State and Iran.

This is why Scottish politician Lord Robertson of Port Ellen, former secretary general of Nato and defence secretary in Tony Blair’s first administration, has warned that independence could impact the broader geopolitical situation.

In an April speech to the Brookings Institution in Washington DC, he said:

The loudest cheers for the breakup of Britain would be from our adversaries and from our enemies. For the second military power in the West to shatter this year would be cataclysmic in geopolitical terms. If the United Kingdom was to face a split at this of all times and find itself embroiled for several years in a torrid, complex, difficult and debilitating divorce, it would rob the West of a serious partner just when solidity and cool nerves are going to be vital. Nobody should underestimate the effect all of that would have on existing global balances and the forces of darkness would simply love it.

His comments were dismissed as alarmist by supporters of a Yes vote but President Obama and Hillary Clinton have also expressed their preference that Scotland remain in the UK. Suddenly, the votes of a small country of five million people could disrupt international relations in ways no one ever expected.

And What of Israel?

One area of foreign policy where there is a degree of certainty is the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The Scottish Nationalists have tended to look more favourably upon the Palestinians than Israel. During the recent Operation Protective Edge, the Scottish Government criticised Hamas’s firing of rockets at Israeli civilians but condemned Israel’s response as “disproportionate”. Ministers pledged £500,000 in humanitarian assistance to the Palestinians, offered to welcome injured Gazans to Scotland for medical treatment in the state-run National Health Service, and called for an arms embargo on Israel. The SNP administration discourages Scottish public bodies from trading with Israeli businesses which operate over the Green Line in Judea and Samaria.

As such, an independent Scotland would likely be more sympathetic to the Palestinian experience than to Israel's security concerns. This would not pose a new challenge for Israel’s foreign ministry, merely add another voice to a now-familiar chorus.

Two points that should give Israelis some hope.

First Minister Alex Salmond is an active foe of anti-Semitism. During the Leveson Inquiry into British media ethics, the SNP leader was asked on the witness stand whether he had ever contacted editors to object to their coverage of current affairs. Somewhat surprisingly, he revealed that he had written to the editors of two of Scotland's leading newspapers to express concerns about anti-Semitic remarks which had appeared on the comment threads of their websites. This is by no means a common practice amongst people of Mr Salmond’s political standing.

Moreover, Scotland has rapidly growing hi-tech and medical technology sectors, areas where it would benefit from cooperation with Israel and the sharing of personnel and ideas. Politics may inflame the passions but economics pays the bills. Whatever objections an independent Scotland might have to Israeli government policy, there are few politicians seriously willing to hurt the Scottish economy just to make grandstanding statements about a conflict halfway around the world.

No one can predict the outcome of the referendum. The race is simply too close to call, with the current poll of polls standing at 51% for No and 49% for Yes. Scotland’s constitutional future might not be the talk of the world’s foreign ministries right now but if Scots vote for independence on Thursday, the impact could be felt far beyond our rolling hills and glens.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.